In 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which sanctioned the incarceration of 110,000 Japanese-Americans in internment camps throughout the western United States. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the United States government viewed incarceration as a way to prevent Japanese-Americans from siding with the Empire of Japan. Many of those incarcerated were American citizens, and this mass suspension of human rights against a perceived other stripped those of Japanese ancestry of their property and dignity without due process.

With the historical gravity of this event, it is surprising to most that Ansel Adams, landscape photographer and conservationist, produced a portfolio of photographs at Manzanar, California, the largest of these internment camps.

This virtual exhibition will examine Adams’s work in Manzanar in the context of his development as an artist, looking at how his earlier portraits and landscapes prefigure his compositions at Manzanar, and how his style matured while documenting Japanese-American incarceration. Throughout his work, Adams captured the quintessential images of the American nation, and in each of these photographs primarily highlighted a sense of resilience and hardiness, both in the landscape and in the Americans who inhabited it. With Manzanar, not only did Adams produce excellent work on the themes of resilience, but he extended his vision of American identity to the Japanese-Americans interned there, arguing that they were just as American as Yosemite, New Mexico, or Old Faithful.

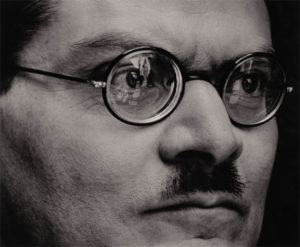

- Ansel Adams, Jose Clemente Orozco, New York City, New York, 1933, 10 ½ x 12 ¾ in., Gelatin silver print, Gift of Virginia Adams, Scripps College

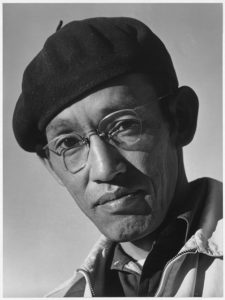

- Ansel Adams, Toyo Miyatake (Photographer), California, 1943, Gelatin silver print, Reprinted from Library of Congress

Portraits, like Toyo Miyatake, (Photographer), make up 200 of the images in Adams’s Manzanar portfolio, and working in Manzanar helped to develop his portrait style further. Though not as well known as his landscapes, Adams had worked often in portraiture, providing the same rich detail he gave American landscapes to the psychologies of those he shot. His photograph of Miyatake, produced at Manzanar in 1943, invites comparison to his 1933 picture of Jose Clemente Orozco. Both men were artists, Orozco a muralist and Miyatake a photographer.

Jose Clemente Orozco was one of Los Tres Grandes, the three Mexican muralists who revolutionized their nation’s art production during the early 20th century. Here, the artist is a portrait of rigid resilience. The camera focuses on his furrowed brow, highlighted by the rim of his glasses. Orozco’s life was defined by the determined expression shown here: he lost his left hand at the age of 21, and then went on to create colossal murals, an artistic form requiring immense physical labor. Here his wound does not matter. One cannot see his missing arm, only his fierce personality.

Toyo Miyatake, (Photographer) is a more straightforward portrait. Whereas Adams cropped his view of Orozco such that only his face is in view, he shoots Miyatake in a more traditional composition, with white space behind him, capturing the hat on his head and his clothes. By cropping his shot of Orozco, Adams produced a vision of the muralist as individual and enigmatic. Toyo Miyatake, (Photographer) captures a direct, stalwart expression. Miyatake’s eyes, with a simple confrontational gaze, represent the spirit of someone insulted but not destroyed by incarceration.

Both represent resilience, Miyatake as an artist surviving internment, and Orozco as one who worked despite his wound.

- Ansel Adams, School Children, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, 1943, Gelatin silver print, Reprinted from Library of Congress

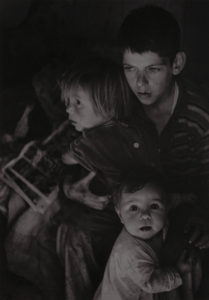

- Ansel Adams, Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California, 1944, 13 5/8 x 9 5/8 in. , Gelatin silver print, Gift of Virginia Adams, Scripps College

Adams uses multiple-subject portraiture in his Manzanar work, a theme he would later revisit. In School Children, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, three girls hold their books as they stand before an unidentified canvas-and-wood building. It is unclear if they are gathered before their school, their place of residence, or an arbitrary structure in the internment camp at Manzanar. Adams was not allowed to photograph the barbed wire that surrounded the camps, and so he had to critique conditions through allusion. Here, the padlock hanging by the rightmost girl’s head insinuates her captivity.

Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California was shot a year after School Children, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California. Though they share similar subject matter—three children under oppressive conditions—the compositions are dissimilar, with Trailer Camp Children casting its figures in haunting shadows rather than in the crisp detail used in School Children. Though the trailer camp children are decontextualized from their surroundings, their expressions allow one to sense the environment they were raised in. This environment, though, is hazy and dark. There is no specific cause of their suffering, only the interminable threat of poverty, whereas with School Children the anonymous barracks point a clear finger at government practices.

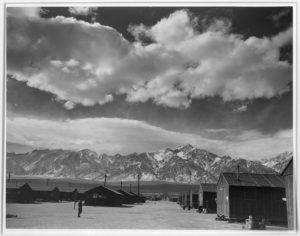

- Ansel Adams, Manzanar Street Scene, Spring, 1943, Gelatin silver print, Reprinted from Library of Congress

- Ansel Adams, Saint Francis Church, Rancho de Taos, New Mexico, 1929, 28 x 24 in., Gelatin silver print, Gift of Virginia Adams, Scripps College

Portraits tell the individual lives of those interned, but it is Adams’s landscapes that best capture the existential horror of the camp. The balance of landscape and barracks in his Manzanar image is important. While Adams uses the backdrops of the mountains in Inyo County as a means of highlighting the drama of internment, he foregrounds the prison conditions in much of his work. This powerful mixing of architectural photography is prefigured during Adams’s residence in New Mexico.

In the introduction to Born Free and Equal, his book on Manzanar, Adams said, “I believe that the acrid splendor of the desert, ringed with towering mountains, has strengthened the spirit of the people of Manzanar.” In Manzanar Street Scene, Spring, Adams focuses on the terrain rather than the people. A single figure walks through an otherwise empty street. The camp is as barren as its desert surroundings, and the white sand of the street matches both the snowcaps in the distance and the ominous clouds overhead. Manzanar becomes a ghost town, a lonely wasteland.

Manzanar Street Scene, Spring places the barracks compositionally at odds with the natural world—they take up only the lower part of the frame, and are dwarfed by the mountains far away.

St. Francis Church, Taos, New Mexico, an early work from his residence in New Mexico, instead synthesizes the earth and the adobe church Adams elected to shoot. New Mexico’s unique adobe structures fascinated Adams, and were a subject he would revisit often in his career.

- Ansel Adams, Monument in Cemetery, Mt. Williamson, 1943, Gelatin silver print, Reprinted from Library of Congress

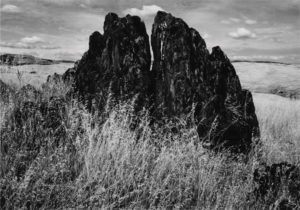

- Ansel Adams, Metamorphic Rock and Summer Grass, Foothills, The Sierra Nevada, California, 1945, 9 ½ x 13 ½ in., Gelatin silver print, Gift of Virginia Adams, Scripps College

Manzanar both expanded Adams’s practice and provided newfound maturity to old themes. Monument in Cemetery, Mt. Williamson, includes a traditional Adams landscape, but also the compositional elements of still life and architectural photography. Adams uses a Japanese gravestone and savage desert conditions to metaphorically allude to the resilience of those interned. The grave reminds the viewer of those who lost their lives in Manzanar. Yet, the composition also suggests hope. In the background, tucked between the gravestone and the mountains, a vast, scrub-dotted desert stretches horizontally through the frame. While the terrain is bleak, the focus is on the grave, rising above the desert to become another peak in the mountain backdrop. Here, Japanese-American identity elevates itself beyond American barbarousness and asserts itself as among the nation’s better angels.

Adams experimented with his compositions at Manzanar, and with this new matured vision of his central theme, the resilience of America and its enduring landscapes, he committed himself to more aggressive lobbying for conservation, in 1946 embarking on a project to shoot photographs of every national park. Metamorphic Rock and Summer Grass, Foothills, The Sierra Nevada, California is indebted to the composition in Monument in Cemetery, Mount Williamson. A small rock sits in a field of grass. The rock’s crevassed form monopolizes the frame, rising up into the clouds. As a crag-ridden stone in the middle of a windswept plain, it has survived years of erosion. There is something quintessentially American about the field surrounding the rock—waves of amber grain quoted in wild grass rather than farmland. Once more, the landscape becomes a stand-in for a cohesive American identity.

With landscapes, Adams suggested the timeless qualities of nature, and with his portraiture he did the same for human traits, affirming resilience, individuality, and resistance as core, eternal parts of the human condition. His portraits and landscapes inform each other, and seeing them as separate elements cheats his portraits out of their monumentality and his landscapes out of their moral humaneness. Adams did not want to capture the curvature of either human or cliff faces, but the soul of the nation as seen both through its natural resources and its people. Photographing iconic images of the nation’s beautiful features, he then turned his lens towards Manzanar and averred that Japanese-American internment was beneath so great a nation.

David Kuhio Ahia, PO ’18

Getty Multicultural Undergraduate Intern

We are grateful to the Virginia Adams Trust for the gift of the Ansel Adams Museum Set and to Michael Whalen for facilitating the gift, which was the source of several of the photos shown here.