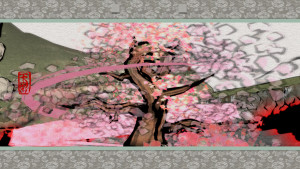

An in-game screen shot of Amaterasu and landscape (detail), “Okami,” displays many commonalities with the traditional subject matter and compostion of Japanese prints. Here, both subjects, bedecked with colorful symbols, face left, toward a waterfall and rocks. Overhead, the branches of a flowering cherry tree arch over each of them. The path created by the line of rats in Chikanobu’s work is echoed by the path to the right of the wolf. A sense of mystery and magic emanates from both images.

Yoshu Chikanobu, “Snow, Moon, Flowers: No. 30 Yamashiro, Flowers of Kinkaku-ji, Princess Yuki,” 1884, woodblock print, ink on paper, 12 13/16 x 8 5/6 in., Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Ballard, Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Imagine a world filled with beautiful landscapes, flowers, and people. Places where theater and dancing women in elaborate kimonos entertain as customers drink and tell tales of heroes and battles of the past. This vision of the world is Ukiyo-e or The Floating World. Ukiyo-e is a popular style of Japanese woodblock prints produced in Japan in the 17th to 19th centuries. Even today, Ukiyo-e continues to inspire new art forms of the 21st century. In particular, the graphical style of one video game, Okami, is heavily influenced by sumi-e (ink wash paintings) and Ukiyo-e. However, Okami and Ukiyo-e share more than just a common artistic style. Ukiyo-e and video games both went through a similar artistic evolution in that they grew out of purely commercial ventures. Neither was highly valued as art for its time.

Ukiyo-e prints emerged in the 17th century mainly as a profit-making venture: the result of technological advances. The development of printing using woodblocks allowed publishers to produce books and art at an extraordinarily faster and cheaper rate than ever before. To put things in perspective, one print cost only as much as a bowl of soup. These prints were primarily aimed at the masses and served as a form of advertisement, government propaganda, and entertainment. Video games, too, emerged as a result of advances in technology—in this case, the development of computers. The games serve mainly as a commercial entertainment product. Yet, they have also been recognized as art. In fact, the U.S government formally recognizes video games as an art form, though most of the general public does not.[1] This was true of 17th century Japanese audiences as well. Prints were not considered to be high art by the Japanese. When, by 1968, Ukiyo-e prints had faded in popularity in Japan, it was the Europeans, specifically the impressionist painters, who, in the 1870s, were first to recognize their value. Not until the Europeans began to see merit in Japanese prints did the Japanese start to recognize their worth.

Moreover, Okami and Ukiyo-e are linked even more inextricably. Graphically, Okami is grounded in the artistic styles of Ukiyo-e and sumi-e. For example, instead of a realistic aesthetic, Clover Studio (creators of Okami) created a game that would resemble a painting. Heightening that effect, the player paints as a key function of the game using one of the primary elements of the game, the celestial brush. With this brush, the player creates patterns on the screen, which then translate as the various powers of the protagonist, Amaterasu. Creating a / pattern would slash an enemy while an O pattern would make a cherry blossom tree bloom.

Okami’s plot draws on various elements of Japanese folklore and Shinto religion, just as Japanese woodblock prints did. Amaterasu, the protagonist of Okami, is the sun goddess of the Shinto faith, personified as a white wolf in the game. She helps the hapless Susanoo (the Shinto storm god) slay the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi. The depiction and retelling of Japanese legends was a staple in Ukiyo-e prints, used as entertainment and as a way of perpetuating beloved stories. Okami is a modern-day extension of this same practice, transforming classical Japanese legends into a form modern audiences find relevant.

Today, Ukiyo-e prints are prized. Routinely exhibited at many prominent museums all around the world, they are also highly valued monetarily. Perhaps the most famous print is Hokusai’s Kanagawa Oki Nami Ura (Under the Wave off Kanagawa), which Christie’s sold for $68,000.[2] Museums collect these pieces in great numbers, with the largest private collection, totaling over 100,000 prints, at the Ukiyo-e Museum in Japan. At Scripps alone, thanks to the efforts of Professor Bruce Coats, the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery has a collection of 2,400 prints, with more continually being added. Scripps’ collection of Japanese prints is a popular highlight of the Gallery’s collection. Japanese prints make up almost a quarter of the entire collection, which began in 1949 as a gift to the College from Mary Wig Johnson. Since then, the Gallery has held numerous exhibitions featuring the print collection, most recently in 2012 with Genji’s World and the Chikanobu exhibition in 2006. The Gallery is currently curating an exhibition on Noh theater prints that will open in 2016.

Though not held in the same regard as Ukiyo-e, there is a growing appreciation for video games as an art form in the United States. For example, the venerable Smithsonian recently curated the exhibition, The Art of Video Games.[3] In addition, the Microsoft Theater hosted Distant Worlds in 2015. This concert featured the game music for the popular video game franchise, Final Fantasy. Grammy winner, Arnie Roth, conducted the LA Philharmonic for the performance.[4] These may be indications that, just as it took the Japanese time to appreciate the value of Ukiyo-e, one day in the not-too-distant future, the art world may well recognize the aesthetic value of video games.

[1] Seth Schiesel, “Supreme Court Ruled; Now Games Have a Duty,” The New York Times, last modified June 28, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/29/arts/video-games/what-supreme-court-ruling-on-video-games-means.html?_r=0

[2] “Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849),” Christie’s, accessed August 5, 2015, http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/prints-multiples/katsushika-hokusai-kanagawa-oki-nami-ura-5180476-details.aspx

[3] “The Art of Video Games,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed August 5, 2015, http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2012/games/

[4] “Distant Worlds: The Music from Final Fantasy,” Microsoft Theater, accessed August 5th, 2015, http://www.microsofttheater.com/news/detail/distant-worlds-music-from-final-fantasy

Okami images courtesy of ©Capcom Co, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Crystal Yang, Getty Visual Resource Intern, Summer 2015