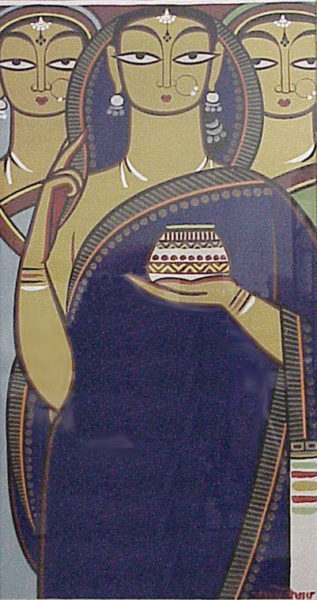

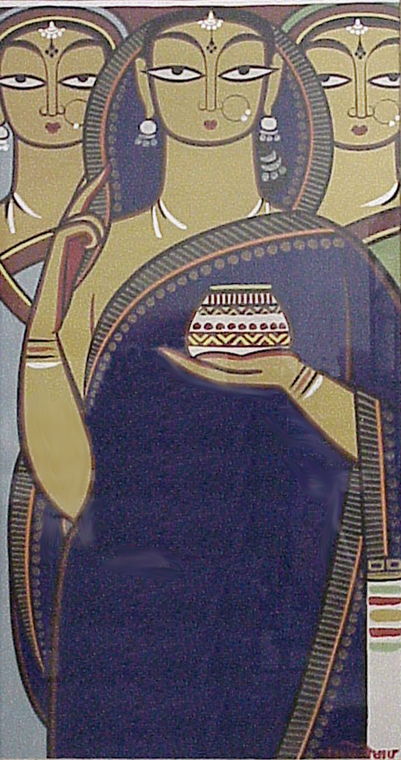

Jamini Roy, “Three Bengali Women,” c. 1965, acrylic on paper, Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Netra Bhat (USC ’23), Getty Collections/Conservation Intern, Summer 2021

The three works below engage with representations of Indian rural life in its varying forms.

William Witt, an American, photographed poverty in rural India while he was stationed there during World War II. His lens is that of an outsider’s—his Western gaze prompts discomfort in the Faces of India’s two women, which can be seen in the way they reach for their veils, covering their faces for the camera. Whereas prominent Indian modernist painter Jamini Roy’s Three Bengali Women stand tall in their traditional sarees and look directly at the viewer with their veils pulled back, unlike the women in Witt’s photographs.

William Witt (1921–2013)

Faces of India, 1943

Gelatin silver print on paper

14 x 11 in.

Gift of Sally Strauss and Andrew E. Tomback

Scripps College, Claremont, California

2019.22.160

William Witt was stationed in India during WWII, and inspired by documentary photography, began his photo career on the subcontinent. Witt portrays a throng of veiled women and their children. The photo is perhaps a snapshot of how the world imagined a stereotypical rural Indian setting, as scenes like this are often the ‘face’ of India.

Jamini Roy (1887–1972)

Three Bengali Women, c. 1965

Acrylic on Paper

29 1/4 in. x 15 1/2 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovichi

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.2.1

One of the most celebrated Indian modernists, Jamini Roy’s signature bold, black calligraphic brushstrokes and large, almond-eyed women seem to pop from the paper. Although he was academically trained in classical Western painting at the Bengal School of Art in India, Roy began to look toward native Bengali folk art to develop his iconic primitivist style, which we see in this work. His limited palette consists of earthy colors made from locally found minerals and plants, like tamarind seeds.

William Witt (1921–2013)

Faceless Woman, India, 1943

Gelatin silver print on paper

14 x 11 in.

Gift of Sally Strauss and Andrew E. Tomback

Scripps College, Claremont, California

2017.12.91

This woman captured by Witt has her face masked by a veil and is performing what is possibly a daily chore of pumping and pouring water from a communal tank to take to her home.

The three works below place Jamini Roy’s Cow and Krishna alongside Indian bronzes from circa 1800 to represent aspects of what the modernists were attempting to revive.

The ball in the hands of the god Krishna, seen in both the bronze and Roy’s painting, is symbolic of the story where the young deity steals lumps of butter from neighboring houses. Such mischief humanizes him. These stories live on in the rural consciousness and were what modernists like Roy referenced in order to connect urbanites to village scenes, creating a homogenous nationalism. Indian freedom fighters, including Mahatma Gandhi, idealized folk arts and handicrafts (like the bronzes seen below) as the cultural heart of India. Roy helped promote this ideal, using his unique works and self-made paints to protest the industrialization that accompanied colonization.

Jamini Roy (1887–1972)

Cow and Krishna, c. 1950

Gouache on Paper

12 in. x 16 3/4 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovichi

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.2.5

The hypnotizingly large eyes of Jamini Roy’s cow draw you into this vibrant work, where the artist incorporates whimsy with background motifs. The blue figure on the right is the infant Krishna, a widely revered God in Hindu mythology. Roy aspired to carve out a distinct style for himself, stating “I do not care whether my paintings are good or bad. I want its appearance to be different.”

Crowned Lord Krishna, c. 1800

Bronze

2 3/4 in. x 2 1/2 in. x 2 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovici

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.3.8

Brahma Candle Holder, c. 1800

Bronze

2 1/2 in. x 2 3/4 in. x 2 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovici

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.3.14

These bronzes of the divine child Krishna and the worshipped cow Nandi (in this case, in the form of an incense holder) are household items in India, often placed in prayer rooms.

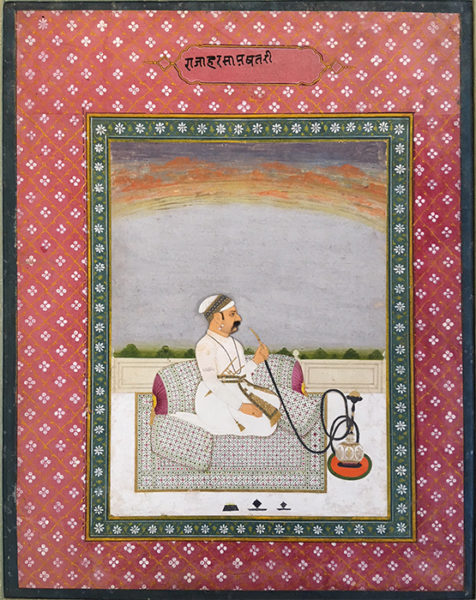

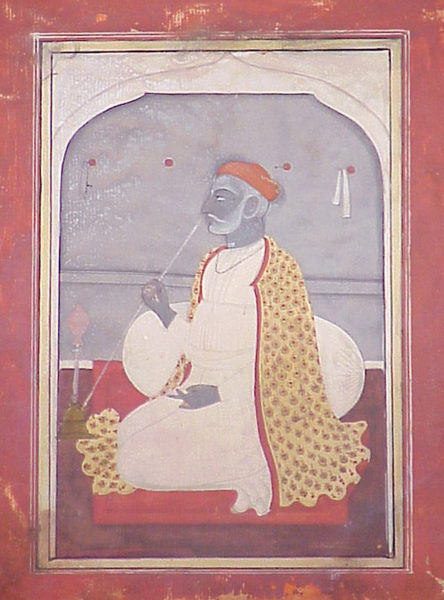

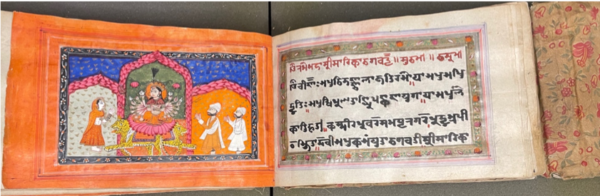

Miniature paintings like the ones below flourished during the reign of the Mughal Empire in India (1526-1857). Hookah or opium pipe smoking in a courtly scene was prominent in Mughal paintings, due to the commonality of the practice among emperors and their penchant for commissioning art.

As seen here, Mughal miniatures were highly detailed, sometimes painted with brushes consisting of a single hair. The labor-intensive quality of these miniatures required artistic collaboration and division of work. Similarly, Indian folk art was often produced collaboratively in workshops, a tradition that modern, anti-consumerist artists like Jamini Roy upheld. Prominent modernists like M.F. Husain and Amritha Sher-Gil drew inspiration from the style of Mughal miniature artists, which were themselves a synthesis of Indian vernacular art’s bright palette, Persian manuscript’s fine detail, and the technical forms of European art. These examples showcase the connectedness of global modernism and how every regional movement played a part in the creation of modernist art.

Portrait of Man Smoking Hookah, c. 1800

Paint and colors on paper

12 x 9 1/2 in.

Scripps College, Claremont, California

2018.9.2

Kneeling Man with Opium Pipe, n. d.

Paint on Paper

8 11/16 in. x 6 9/16 in.

Gift of Mr. Edward Nagel

Scripps College, Claremont, California

1929

Katherine Gilette Osbourne Papers

Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Claremont, California

except that it demonstrates the Devanagiri writing system, which is shared by several languages like Hindi, Sanskrit, Marathi and Pali. The text is interspersed with minutely detailed miniature paintings, which are often followed by intricately decorated and handwritten title pages. It is a religious text, most likely Hindu, since the God Krishna can be identified in blue. The binding consists of a European print, and the text might have been rebound by former owner Ms. Osbourne. The decorative nature of these miniatures and their storytelling capacity were aspects of primitivist artwork that Indian modernists were attempting to revive.

M.F. Husain (1915-2011)

The Triumphant, n. d.

Oil on Canvas

25 3/8 in. x 33 1/2 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovici

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.2.2

One of the best paid Indian painters of his day, M.F. Husain portrayed Indian imagery in contemporary styles like the bold, modified Cubism we see above. Husain was a part of the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) in Bombay (now Mumbai) whose motto was to paint with “absolute freedom.” PAG formed in 1947 during the tumultuous partition of India and Pakistan. The group’s art was never without socio-political commentary on current matters, and Husain was no outlier. In The Triumphant, Husain depicts the royal, majestic Indian elephant perhaps as a symbol of the British Raj finally leaving the subcontinent and the people of India triumphing over colonialism.

Sultan Ali (b. 1920)

Lonely, n. d.

Oil on Canvas

30 in. x 24 1/2 in.

Gift of Mr. Vladimar S. Aronovici

Scripps College, Claremont, California

95.2.3

This piece—an oil painting diverging from formal realism, with its intentional cracks and figurative flaws—encapsulates J. Sultan Ali’s art. Ali trained under the strict confines of classical European painting but felt that overall, the style was too cold. He sought to bring his Indianness into expressionist works that were inspired by tribal communities, Hindu deities, and other religious iconography. The woman in the painting seems calm, serene albeit for the cracks that belie a darker, somber feeling of loneliness. This yearning for art to convey true feeling rather than technical perfection was Ali’s goal, as he states, “I was more concerned with the heart than the head.”

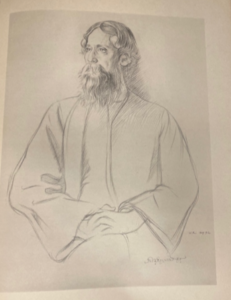

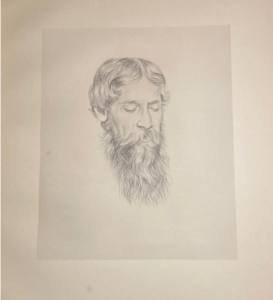

William Rothenstein (1872-1945)

Six portraits of Sir Rabindranath Tagore, 1915

Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Claremont, CA

English painter, printmaker and writer William Rothenstein had a career that intersected with the rise in Indian nationalism. Rothenstein was a war artist, drew portraits of famous people, and was a witness to the Indian modernist movement. He became enraptured with the Bengali poet and artist Rabindranath Tagore, who started the Santiniketan art school in 1901 to “blend the best of Eastern and Western culture.” Rothenstein sketched the above portraits of Tagore when the poet visited him in London.

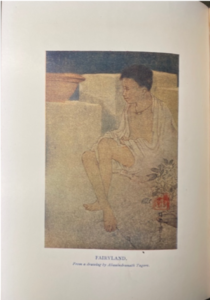

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

The crescent moon: child-poems, 1914

Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Rabindranath Tagore was a Bengali artist, poet, author, song-composer and playwright. In 1913 he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Tagore wrote in Bengali, his native language, and his works, including this one, were translated into English. However, layers of symbolism can be lost in translation. For example, “Fairyland” above references the tulsi (holy basil) plant. Commonplace in Indian homes it connotes scenes of domestic beauty to Indian readers but would lose that emotional impact with a Western audience. His nephew, Abanindranath Tagore, created the poem’s accompanying artwork and founded the Bengal School of Arts which trained modernists like Jamini Roy. Rabindranath Tagore’s appreciation for folk culture was reflected in his work. He became a spokesperson for Indian independence abroad and was seminal in defining Indian identity during the 1900s.

Bibliography

Kumar, R. Siva. “Modern Indian Art: A Brief Overview.” Art Journal 58, no. 3 (1999): 14–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/777856.

“Primitivism and Primitive Art.” Primitivism, Primitive Art: Definition, Characteristics. Encyclopedia of Art Education. Accessed July 25, 2021. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/primitivism.htm.

Mitter, Partha, and Partha Mitter. “The Indian Discourse of Primitivism.” Essay. In The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1922-1947, 29–122. London: Reaktion Books, 2007.

Chatterjee, Ratnabali. “’The Original Jamini Roy’: A Study in the Consumerism of Art.” Social Scientist 15, no. 1 (1987): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3517398.

Mitter, Partha. “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery.” The Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (2008): 531–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2008.10786408.

Santhosh, S. “What Was Modernism (in Indian Art)?” Social Scientist 40, no. 5/6 (2012): 59-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41633810.

Mitter, Partha. Art and Nationalism in Colonial India 1850-1922: Occidental Orientations. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997.

Luntz, Holden. “William Witt ARCHIVES.” Holden Luntz Gallery. Holden Luntz Gallery. https://www.holdenluntz.com/artists/bill-witt/page/4/.

“Bill Witt Archives – Be-Hold.” Be-hold. Be-hold. https://www.be-hold.com/photographers/20th-century/bill-witt/.

Eaton, Natasha. “”Swadeshi” Color: Artistic Production and Indian Nationalism, Ca. 1905–ca. 1947.” The Art Bulletin 95, no. 4 (2013): 623-41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43188857.

“Virtual Tour Explore the Life and Work of Pioneering Artist : JAMINI ROY.” National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. NGMA, April 11, 2020. http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-modern-art-1.asp.

Chatterjee, Indrajit. “Jamini Roy’s Home Studio and Local Paints.” Prinseps. Prinseps, September 29, 2018. https://prinseps.com/research/jamini-roy-painting-mediums-local-binder/.

Tubach, Surya. “The Astounding Miniature Paintings of India’s Mughal Empire.” Artsy, April 30, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-astounding-miniature-paintings-indias-mughal-empire.

Ray, Sharmistha. “The Young Firebrands of Indian Modernism.” Hyperallergic, December 22, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/477316/the-progressive-revolution-modern-art-for-a-new-india-asia-society-museum-2/.

“J. Sultan Ali.” Delhi Art Gallery (DAG). Delhi Art Gallery. https://dagworld.com/artists/j-sultan-ali/.

“J. Sultan Ali.” Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF). Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation. https://jnaf.org/artist/j-sultan-ali-2/.

“J Sultan Ali.” Saffronart. Saffronart. https://www.saffronart.com/artists/j-sultan%20ali.

“Rabindranath Tagore in London.” The Fortnightly Review. The Fortnightly Review, May 23, 2017. https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk/2013/05/tagore-in-london/.