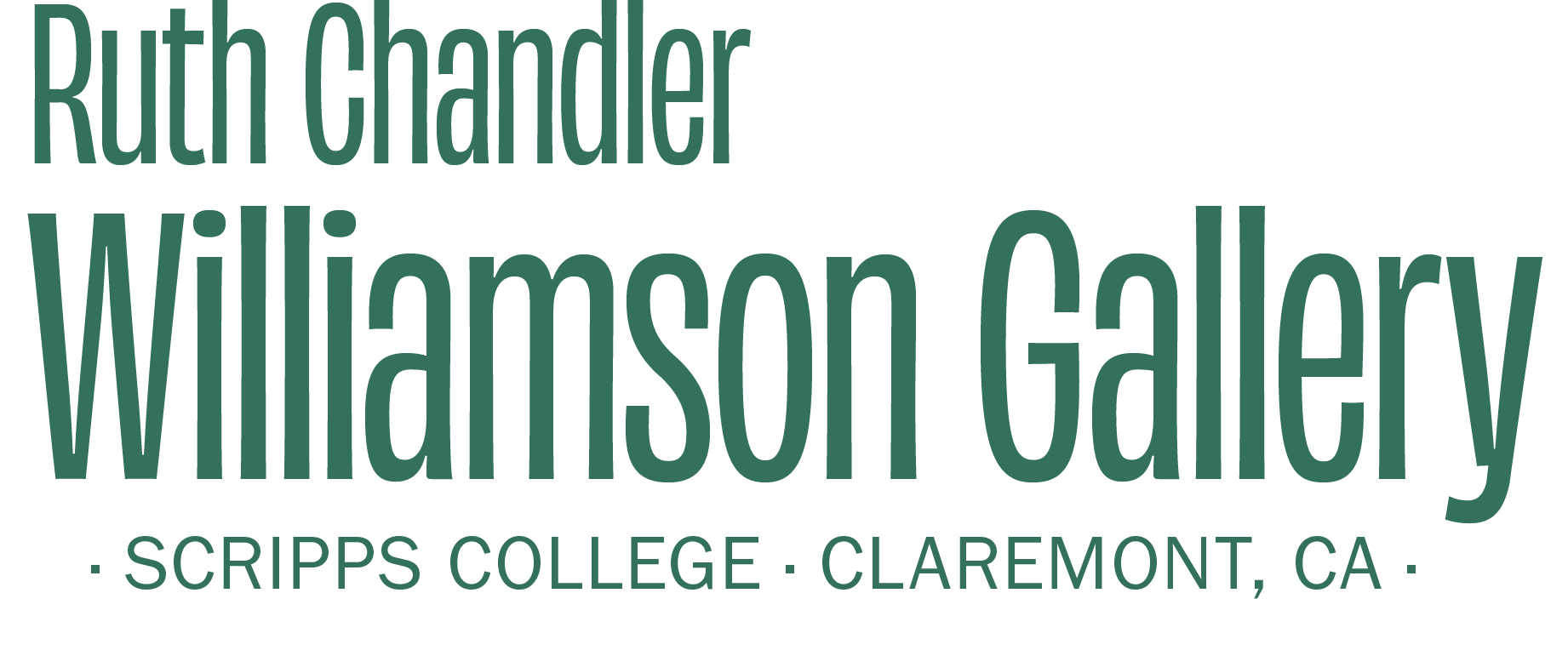

“In the Garden: Cornucopia”, 2004-2007. Spit bite and aquatint on Rives BFK paper. 32 X 25 inches. Mark Mahaffey, Master Printer Edition 1/25. Gift of Nancy Macko.

In 1986, Nancy Macko joined the Scripps faculty as a Professor of Art. Chair of the Department of Art and Art History between 1998-2003, Macko has directed the Scripps Digital Art Program since 1990 and in 2004 was appointed chair of the Gender and Women’s Studies Department. A native of New York, she received her undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin, River Falls. Continuing her studies at the University of California at Berkeley, she earned a MA and MFA in Studio Art as well as an MA in Education. A practicing artist since the early 1980s, Macko has been an active figure in the feminist art movement and the art community in California, serving on the Exhibitions Advisory Committee for LACPS (Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies) (1994-6); the Art Advisory Committee for the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery (1996-8); the national Board of Directors of the College Art Association (1994-8); ArtTable (2002-6); and the Advisory Board of the Southern California Women’s Caucus for Art (2003-6).

As a graduate student, Macko contributed to feminist artist, Judy Chicago’s major piece, The Dinner Party (1979). Likening the experience to life in the matriarchal society of a beehive, Macko commented, “Anything that had to get done was being done by women. I had seen women able to accomplish things, but the whole idea of being completely reliant on other women was a revelation.” The experience of working in a sort of micro society independent of a male presence inspired Macko’s interest in feminist utopias. As part of her research career, which informs her artistic work, Macko examines evidence of matriarchal cultures in existence between 5000 and 3500 BC. As Macko states, “it is still a very patriarchal world, and women don’t have equal rights. I’m curious about whether there was ever a time when things were reversed”. In this manner, the honeybee’s matriarchal society fascinates Macko. Furthermore, the discovery of the term “bee priestesses” coined by Savina Teubal in Hagar the Egyptian: The Lost Tradition of the Matriarchs, provided Macko with a sort of spiritual practice to replace patriarchal religion. Macko uses the themes and images of honeybees and bee priestesses throughout her print work, installations, mixed media and multi-media work.

The image of the bee priestess appears in, In the Garden: Cornucopia, created with master printer, Mark Mahaffey, of Mahaffey Fine Art LLC in Portland, Oregon. The Williamson Gallery recently acquired one of the 25 intaglio prints of the edition. Using two-plate color etching to achieve the subtle color scheme of gold and muted blue, the image is etched into a plate using a spit bite method in which acid is applied directly to the plate to create recesses. The surface of the plate is covered in ink, then rubbed clean leaving the ink resting in the incisions of the plate. A damp piece of paper is then placed on the plate and run through the printing press. With the pressure of the press, the ink is transferred to the paper. Cornucopia highlights Macko’s practice of composing in layers and the repetition of certain images throughout her work, such as the page reinforcement and artifacts from the Cucuteni culture, which she studied in Romania in 1996. True to its title, Cornucopia exudes a feeling of abundance and prosperity. Hidden behind and intertwined with the delicate and feminine flowers, references to the flowered wallpaper from her grandmother’s home, one finds bees, beehives and the image of the bee priestess, a women’s torso emerging from the abdomen of a honeybee, raising her arms in a gesture of divine strength. Writing about her ideas involved in the prints, Macko states, “The works recall a time when the feminine was sacred and women were truly revered.” While she concedes that the reference to her grandmother’s wallpaper may appear to give the print “a sentimental edge,” the image of the bee priestess creates an overall tone of “an active feminine that knows no bounds.” Indeed, this intermingling of femininity and force speaks to the heart of the Scripps student body, an embodiment of strength in womanhood.

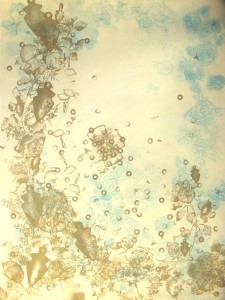

“The First Ten Prime Numbers Suite I: Sixth Prime”, 2006. Plate lithography on Rives BFK paper. 30 x 20¼ inches. Mark Mahaffey, Master Printer Edition 3/10. Gift of Nancy Macko.

Macko’s interest in the science of bee societies led to a curiosity in mathematics, which in turn resulted in her exploration of the intersection of math and art. In her recent work, Macko has explored prime numbers and the phenomenon of prime deserts. In Interstices: Prime Deserts, 2003, Macko worked with math professor, Robert Valenza, of Claremont Mckenna College. Macko and Valenza explored moments linking art and math through their representation of the “space” between prime numbers. A prime number is a positive integer, which can only be divided with no remainder by itself and one. While some prime numbers occur consecutively, such as 59 and 61, in other instances, there are long stretches of whole numbers in which no prime numbers appear. These stretches are known as prime deserts.

During her 2003-2004 sabbatical, Macko created two suites of lithography prints, again with the aid of Mahaffey, entitled, The First Ten Prime Numbers. In the first suite, Macko represents each of the first prime numbers (2,3,5,7,11,17,19,23,29) as arrangements of copper page reinforcements on Rives cream BFK paper. Each arrangement invokes the idea of a growing cluster, constellation, cell or hive. The simplicity of these prints allows the viewer to analyze the representation of the numbers. Discussing Macko’s placement of reinforcements one curator stated, “Macko works by instinct, drawing upon the ideas of Zen composer/ philosopher John Cage, who would maintain that every reinforcement is in exactly the right place but that every other place would also be exactly right.” Thus, Macko’s arrangements are at the same time random and deliberate. Macko discusses the work as a process of creating a hive of one’s own, constructing a universe in dark matter, the fabric of space, or as she envisions it, the sacred feminine. In this work, Macko obliquely links her interest in science, mathematics, the honeybee and the divine matriarch.

Written by Megan Downing (SC ’08), 2007-08 Academic Year Wilson Intern.