Japan Anonymous, Kimono (Woman’s Robe), 1920-1940, silk, 57 in. x 53 in., Scripps College, Claremont, CA

SHIKI: The Four Seasons in Japanese Art

Jan. 30-Aug. 1, 2021

Williamson Gallery, Scripps College

“From the most elaborate folding screen embellished with purple irises to a small teacup painted with a single maple leaf,” notes curator Meher McArthur, “such seasonal references are an integral part of the cultural and emotional lives of the Japanese people.”

INTRODUCTION

The Japanese have long revered the power and beauty of nature. From as early as the 7th century AD, they have expressed and codified elements of nature and the four seasons (Japanese: Shiki, 四季) in their poetry and art. Gradually, a rich literary and visual vocabulary relating to the Four Seasons evolved, with flowers, trees, plants, birds, animals and entire landscapes representing each season and its associated moods and activities.

These seasonal indicators feature prominently in paintings, prints, flower arrangements and garden design and embellish ceramics, lacquer ware, metalwork, clothing and accessories. They also inspire social activities, including annual festivals, entertainment and travel, which are in turn shown in works of art. Most notably, cherry blossoms and wisteria symbolize spring, while the iris and lotus indicate summer, chrysanthemum and red maples autumn, and the camellia and pine tree wintertime. These seasonal symbols are imbued with emotional attributes relating to the natural cycle: the lifting of spirits and hope for love as spring follows winter, an appreciation of coolness during the oppressive summer heat, the melancholy of autumn as plants fade and die, and the resilience associated with bitterly cold winter months.

This exhibition of Japanese art from the Scripps College collection gathers together works featuring the most common seasonal motifs. Traditionally, these works would have been displayed in the home, used to serve food and drink or worn on the person as a way of deepening the connection between the owner and the particular season. From bamboo in the snow on a gilded folding screen to chrysanthemums on a lacquered hair comb, these seasonal references play an integral role in the cultural and emotional lives of the Japanese people.

Long-Sleeved Kimono (Furisode) with Flowers of the Four Seasons

Japan, 1950-1960

Silk crepe with yuzen stenciled designs

Scripps College Collection, T100

Although many Japanese works of art feature specific seasonal symbols, the “Flowers of the Four Seasons” has been a popular motif in paintings, textiles and other artistic media that could be displayed, worn and used all year round. This long-sleeved kimono, or furisode, has cherry blossoms and wisteria for spring on its shoulders, irises and peonies representing summer and chrysanthemums for autumn on its sleeves, and large camellia blooms for winter on the front.

SPRING

ことしより春しりそむる櫻花ちるといふ事はならはさらなん

Kotoshi yori Oh, cherry blossoms

haru shirisomuru who have just this year

Sakurabana begun to understand spring –

chiru to iu koto wa would that you never learn

narawazaranan what it means to scatter!

Waka poem by Ki no Tsurayuki (872-945)

In Japan, spring and autumn are the favorite seasons since they offer respites from the heat and humidity of the summer and the bitter cold of wintertime. Traditionally, spring began at the lunar New Year, the first day of the first month and finished at the end of the third month (the equivalent of February 4th to May 4th), though the season tends to be shorter than three months in reality. According to poetic and artistic conventions, early spring is the time when snow melts, ice thaws and spring mist descends on the landscape. The bush warbler (uguisu) – a small, sparrow-like bird – returns from its winter hideaway, its song signaling the advent of warmer weather. In this season, trees and flowers begin to bloom and turn green. In early spring, plum trees (ume) blossom and willows (yanagi) start to bud, followed by vines of purple wisteria (fuji) and yellow rose-like kerria (yamabuki). The crowning moment of spring is the blooming of the cherry blossoms, the fullness of branches laden with pale pink flowers, followed by the scattering of their petals that serves as a reminder of the transience of life.

In both poetry and art, these various symbols of spring can appear separately or grouped together, often in bird-and-flower pairings like the bush warbler and plum blossom. In addition, poems and images abound with the theme of people gathering to enjoy picnics under the wisteria or cherry blossoms.

Procession of Women Through the Cherry Blossoms (detail)

By Utagawa Hiroshige II (1826-1869)

Japan, 1857

Full-color woodblock triptych print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson, 46.1.168

During the Edo period (1603-1868), processions (gyoretsu) of feudal lords and their entourages were a regular occurrence. These processions between the feudal lords’ provinces and the capital were mandated by the shogun (Japan’s military leader) to control the lords and prevent uprisings. This print by Hiroshige II mimics such processions by depicting women and their attendants along a road passing closely by Mount Fuji. All around them, cherry trees are in full bloom and at the peak of their beauty.

Yamashiro, Flowers of Kinkaku-ji, Princess Yuki, No. 30 from the series Snow, Moon, Flowers

By Yoshu Chikanobu (1838-1912)

Japan, 1884

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Ballard, 93.6.118

The artist Chikanobu created a series of prints, Snow, Moon, Flowers (Setsu Gekka) celebrating the three most visually rich seasons, with winter snow, the autumn moon and spring flowers. In this print, he illustrates a scene from the legend of the beautiful Princess Yuki, the daughter of a famous artist who was captured and tied to a flowering cherry tree in the garden of the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji) in Kyoto. She used both art and magic to escape. With her toes, she drew a picture of a mouse using the flower petals at her feet. The mouse came to life and multiplied, and chewed through the ropes binding the princess, setting her free.

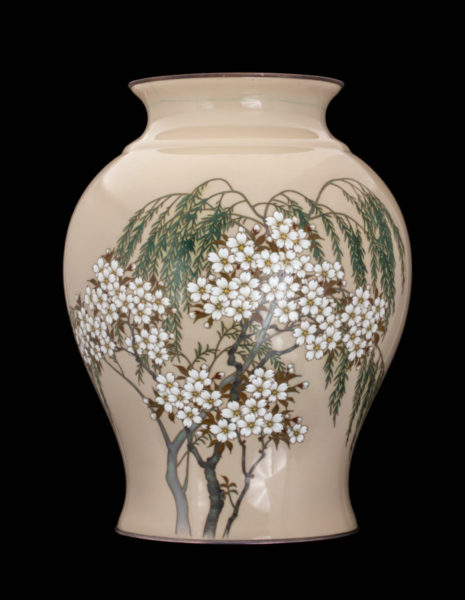

Vase with Cherry Blossoms and a Willow Tree

By Ando Jubei (1876-1956)

Japan, c. 1912

Cloisonné enamels on metal

Scripps College Collection, Gift of R. Scott and Lannette Turicchi, 2011.16.5

This cloisonné enamel vase by Ando Jubei depicts cherry blossoms with a willow tree—two Japanese symbols of spring. In cloisonné, slender metal wires are attached to a bronze or copper vessel to form enclosures, or “cloisons,” which form the outlines of patterns, sometimes geometric but often floral. The enclosures are filled with colored powdered enamels and then fired to melt the enamels into a glass-like finish. The Japanese began making cloisonné around the late 17th century, and by the end of the 19th century, Japanese cloisonné reached its Golden Age and was greatly admired in the West. The factory Ando managed in Nagoya produced some of the most superb cloisonné enamel pieces, such as this vase, for display at the great world exhibitions.

Court Lady of Hotoku Era from the series Thirty-Six Selected Beauties

By Mizuno Toshikata (1886-1908)

Japan, 1891

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, 2017.1.81

Wisteria is a vine native to East Asia, and its flowers typically bloom in late April to early May in Japan. As well as the season of spring, the flowers also symbolize love, longing and endurance, probably because of the strong attachment wisteria vines form on trees, trellises and other structures. This print depicts a court lady of the Hotoku era (1449-1452), standing on a veranda gazing into the distance, perhaps dreaming of being with a loved one. The purple of her outer kimono perfectly matches the hue of the wisteria blossoms.

SUMMER

すず風や 力いっぱい きりぎりす

Suzukaze ya Refreshing breeze

Chikara ippai With all his strength

Kirigirisu The cricket

Haiku poem by Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828)

Summer is not the most pleasant time of year in Japan; it is generally intensely hot and humid, with periods of heavy monsoon rains. In the traditional calendar it extended from the fourth through the sixth month (the equivalent of May 5th to August 6th). Because it has always been a hot and uncomfortable season to be outdoors in nature, summer, like bitterly cold winter, has not featured as prominently in poetry or the visual arts as spring and autumn. When it has been the subject of poetry or paintings, the theme has often focused on the coolness that comes from a refreshing breeze or the evening air, as in the above poem and in woodblock prints depicting women sitting by a river holding a paper fan.

The bird that most often symbolizes summer in literature and art is the cuckoo (hotogogisu), its song associated poetically with longing, either for a lover or a hometown. Early summer is often suggested by deep purple irises, which grow in swampy areas, and are associated with the 8th-century courtier and poet Ariwara no Narihira, who was banished from the capital and composed a poem about these flowers to express his longing for home. Mandarin orange blossoms (tachibana), with their evergreen leaves, golden fruit and sweet fragrance, also feature in summer imagery, as well as the peony (botan), a multi-petalled flower also associated with feminine beauty. The lotus (renge), which blooms pure white from the muddiest pond water, also suggests coolness in summer as well as the Buddhist belief that we can all attain spiritual perfection.

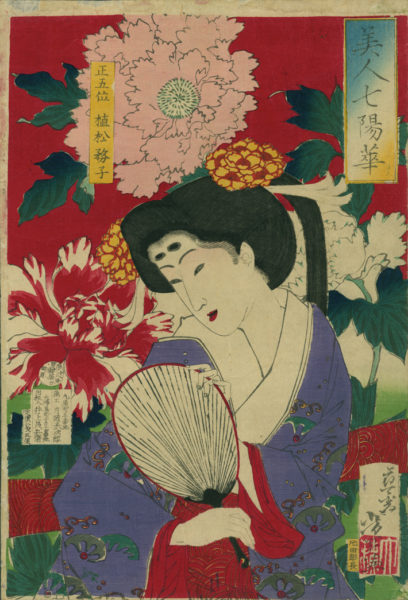

Peony Uematsu Chikako from the series Beauties and the Seven Bright Flowers

By Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Japan, 1878

Full color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, 2008.1.52

In the late 1870s, the artist Yoshitoshi designed a series of prints called Beauties and the Seven Bright Flowers, which paired beautiful women from the Imperial Court with the most popular seasonal flowers. Here, the Lady Uematsu Masako (or Chikako) is paired with peonies, a flower that has long been associated with feminine beauty and a symbol of summertime. She is shown in a colorful kimono carrying a paddle-shaped hand fan (uchiwa) to help her stay cool in the summer heat.

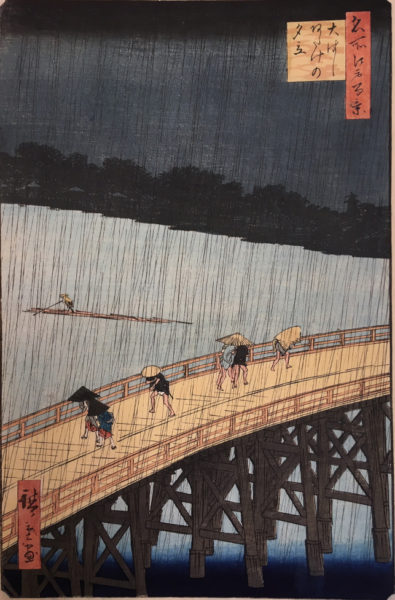

Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge, No.52 from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

By Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Japan, 1857

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Jim and Ann Ach, 2019.4.1

This famous print by Hiroshige depicts pedestrians caught in a summer downpour as they cross a bridge in Edo (now Tokyo). Japan has a rainy season during June and early July. It is known as tsuyu (梅雨, also pronounced baiu), literally meaning “plum rain” because it coincides with the season when plums ripen. Hiroshige’s strong sense of composition and his ability to design printed rain so that we can almost feel it lashing down on us has made this print one of his most celebrated images. It inspired Vincent van Gogh to create a copy in oils thirty years later.

AUTUMN

のに山にうかれうかれてかえるさを

ねやまでおくる秋のよの月

No ni yama ni Across the fields and hills

ukare ukarete my spirits buoyed with joy,

kaerusa o I return to my bedroom

neya made okuru accompanied by

aki no yo no tsuki tonight’s autumn moon.

Waka poem by Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875)

Autumn has always been the most popular season for poets and artists since this is the time of year when temperatures cool, outdoor activities resume, and the colors of nature are at their most dramatic. Crimson maples and gingko leaves vie with evergreens like pine and bamboo against a bright blue, cloudless sky. The season has traditionally extended from the seventh month to the ninth month (the equivalent of August 7th to November 6th) and includes the rice harvest and celebrations such as the Star Festival (Tanabata) on the 7th day of the 7th month and the annual rite of viewing the harvest moon (meigetsu) in the middle of the 8th month.

Maple leaves (momiji) are the most popular autumn motif, either in their dazzling fullness on trees or floating on the surface of rivers such as the Tatsuta River in Kyoto. Chrysanthemums (kiku), bush clover (hagi) and autumn grasses (akikusa) such as miscanthus (susuki) feature prominently, either alone or paired with deer (shika), wild geese (kari) or insects such as crickets (kirigirisu), all of which are known for their wistful cries. These motifs may also be set against a large, full autumn moon (aki no tsuki). Though the full moon appears all year round, it is most often linked with autumn, the harvest and a sense of melancholy at the passing of the year and the approach of the cold winter months.

Beneath the Autumn Leaves, Chapter 7 from The Tale of Genji

Unsigned

Japan, 19th century

Ink and pigment on gold leaf on paper, mounted as a four-panel folding screen (byobu)

Scripps College Collection, 2018.18.2

This four-panel folding screen is decorated with an autumn scene from The Tale of Genji. The scene is from Chapter 7 of the novel and is set at the Suzaku Palace in the tenth month. Under the autumn leaves, Genji performs a dance along with another courtier, To no Chujo, and garners much admiration from the Emperor as well as various ladies of the court, a number of whom have been romantically involved with Genji. The painting in mineral pigments on gold leaf is in the Tosa style, the native Japanese style of painting typically used to depict scenes from Heian period (794-1185) literature and the Heian court. The lines are very fine, mineral pigments are applied densely in certain areas, and scenes are often shown aerially, from a bird’s eye viewpoint. In this screen, gold clouds also frame most of the scene.

Chrysanthemums and Stream

By Ohara Shoson (active 1877 – 1945)

Japan, c. 1926

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Mrs. Frederick S. Bailey, 54.1.105

This vibrant print depicting chrysanthemums is by Ohara Shoson (1877-1945), also known as Ohara Koson, a painter and print designer who was part of the Shin Hanga (“New Prints”) Movement of the early 20th century. Most of his prints feature birds and animals. Here, he depicts pink and yellow chrysanthemums hanging over a winding river, an image that very vividly evokes the joy and coolness that this season can bring, as well as recalling the Chinese legend about spring waters surrounded by chrysanthemums bestowing long life on those who lived nearby.

Comb with Fans and Chrysanthemums

Japan, 1930s-40s

Paint with mother-of-pearl on plastic

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Ralph Riffenburgh in Honor of Angelyn Kelley Riffenburgh, 2013.7.58

This dramatic comb was made in the early 20th century. It was formed with a mold out of plastic (probably Bakelite) and then painted a vibrant red in imitation of lacquer, with details in mother-of-pearl. The larger chrysanthemums were formed in the mold, while the smaller mother-of-pearl mums inside the fan-shaped sections were probably affixed with an adhesive. Although plastic is a cheap, ubiquitous material today, in the 1920s and 1930s it was still an exciting and modern material that was hard to come by, and plastic jewelry and other ornaments were very popular around that time. It would have been worn during the autumn months for special occasions.

WINTER

冬枯れ や 世は一色に 風の音

Fuyugare ya Winter solitude

yo wa isshoku ni in a world of one color

kaze no oto the sound of wind.

Haiku poem by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694)

Winter in Japan can be a severe season characterized by cold, frost and snow, particularly in northern Honshu and Hokkaido. Traditionally the season extended from the tenth to twelfth months of the lunar calendar (the equivalent of November 7th to February 3rd), and its harsh conditions made it a relatively unpopular season among earlier Japanese courtiers and poets, who essentially considered it as cold and lonely. In poetry, cold early winter rains (shigure) and the falling snow (yuki) are sometimes winter subjects, with snowflakes sometimes being compared with scattering cherry blossoms. In art, snowy landscapes were popular themes in monochrome ink paintings and in the woodblock prints of artists like Hiroshige, who skillfully captured the silence of the snow in urban and rural landscapes.

As well as snow, symbols of winter most famously include plum (ume or bai), bamboo (take or chiku) and pine (matsu or sho). Pine is an evergreen, bamboo bends with the wind, while the plum blooms in cold temperatures. Collectively, they are known as the “Three Friends of Winter,” or shochikubai in Japanese. In this grouping, which originates in China, they represent strength and resilience. Camellias (tsubaki) also bloom in the wintertime, so are also associated with this chilly season.

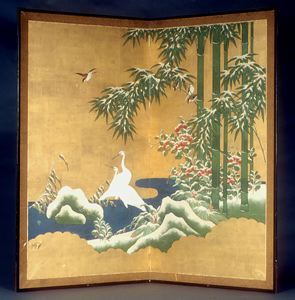

Screen with Cranes, Bamboo, Camellias and Snow

Unsigned

Japan, late 19th or early 20th century

Paint and gold leaf on paper mounted as a two-panel screen (byobu)

Scripps College Collection, 0255

This two-panel screen features plants and birds of winter, including two white cranes, pine trees, bamboo, sparrows and camellias in the snow, all painted onto a ground of gold leaf. Often, these motifs are depicted individually or in pairs – like cranes and pine trees, or sparrows and bamboo – but here we see them all together to create an idyllic scene of nature in the wintertime. Although white is the predominant color in winter scenes, the red camellias peeking through bamboo and sprinkled with snow provide some dramatic color accents.

Fashionable Pastimes of the Four Seasons (Furyu Shiki): Winter

By Kikugawa Eizan (1787-1867)

Japan, c.1830

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson, 46.1.97

The artist Kikugawa Eizan followed the style of Kitagawa Utamaro (c.1753-1806), whose portrayals of beautiful women (bijin) of the pleasure quarters are some of the most admired examples of ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world. Eizan’s beauties have much of the elegance of Utamaro’s beautiful women but their facial expressions are slightly sterner, as is typical of many 19th century bijin prints. This winter scene shows two women wearing many layers of kimono and huddled under an umbrella to protect themselves from the snow, which is depicted very rhythmically as puffy flakes falling against the evening sky and in wave-like piles on the ground all around their feet.

Tale of Genji: Murasaki and Genji Enjoying the Snow

By Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Japan, c. 1854

Full-color woodblock print

Scripps College Collection, Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson, 46.1.170

In this triptych (three-part print), the artists Kunisada (left and right figure prints) and Hiroshige (the garden in the center) collaborated to create an Edo-period take on Chapter 20 (“Morning Glory,” or “Asagao”) from The Tale of Genji. In this chapter, Genji visits Lady Murasaki, his greatest love, at his Nijo mansion one early spring evening and is impressed by how beautiful the garden looked in the snow. Genji declares, “People make a great deal of the flowers of spring and the leaves of autumn, but for me a night like this, with a clear moon shining on snow, is the best and there is not a trace of color in it.” Here, Genji and Murasaki, dressed in fabulous kimono, watch from the palace verandah as a group of young women build a giant rabbit out of snow, the one at the front shaping the bunny’s head with a trowel and positioning a red lacquer sake cup to make its eye.

Vase with Plum Blossoms

By Kawade Shibataro (1856-c.1921)

Japan, c.1910

Cloisonné enamels on metal

Scripps College Collection, 2011.16.7

This spectacular cloisonné vase was made by the artist Kawade Shibataro (1856-c.1921), one of the major cloisonné artists of the turn of the last century. Kawade worked at the Ando cloisonné factory in Nagoya and is known for having innovated several cloisonné techniques. These include moriage, in which enamels are built up beyond the surface wires to add modeling and dimensionality to designs. In this beautiful vase, Kawade completely covered the surface of the vase with a design of white plum blossoms against a dark winter sky. Although the overall palette is black and white, a network of finely textured brown and green branches add depth and structure to the overall composition. The drama and energy of this vase celebrates the hardy plum blossom and its message of hope and light at the darkest time of the year.

Slider Image: Utagawa Kunisada, Tale of Genji: Murasaki and Genji Enjoying the Snow, 1854, woodblock print, Scripps College Collection, Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson.