Banner designed by Cecelia Blum SC ’24

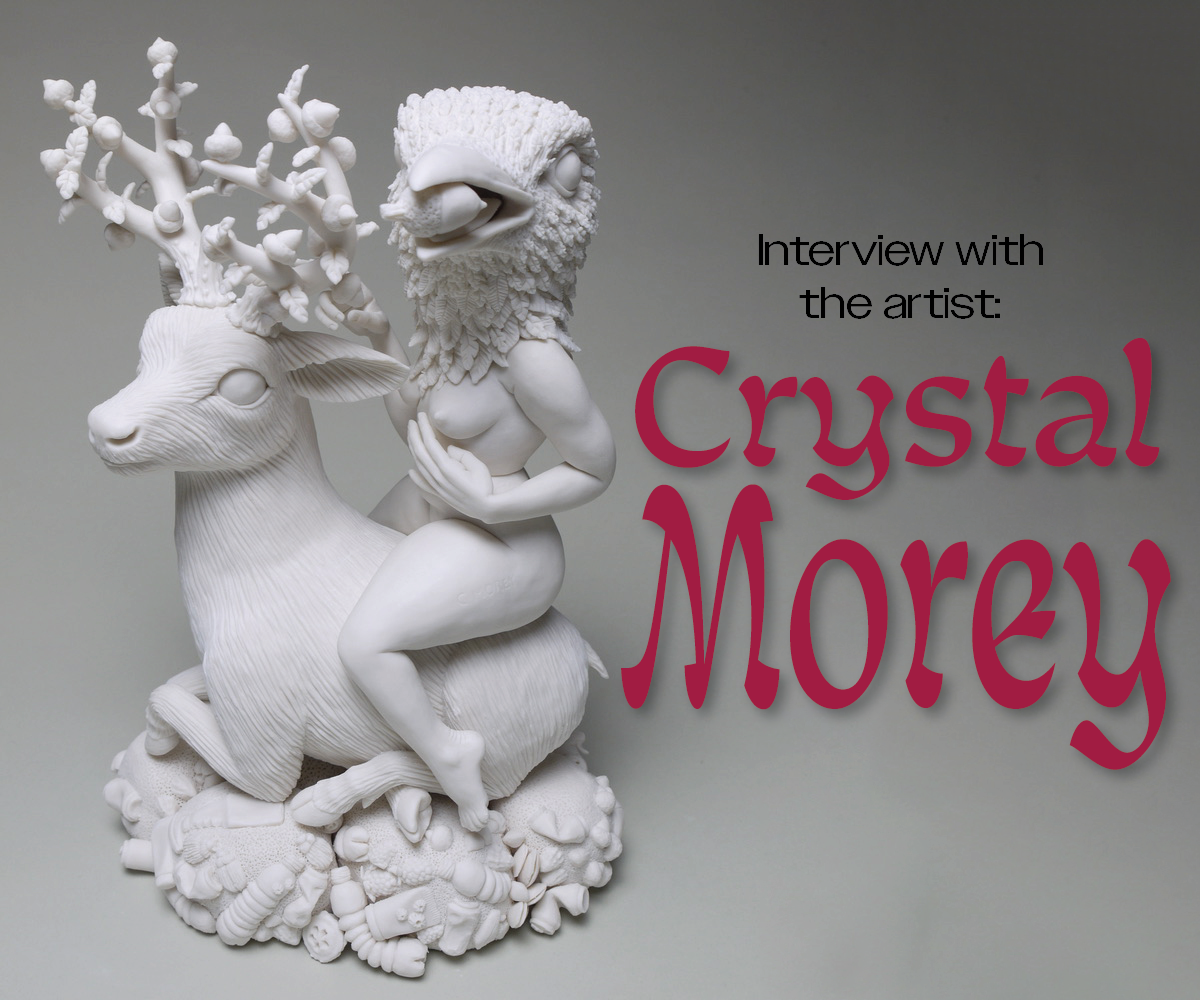

Crystal Morey’s latest series, RePlanting, features porcelain sculptures that explore the interconnection and precarious balance between humans, flora, and fauna. While her work focuses on weighty topics, such as endangered species and climate change, her pieces are imbued with whimsy and hope for a more consciously interconnected future. Morey’s sculpture, Scrub Jay and Deer, was featured in the American Museum of Ceramic Art (AMOCA) exhibition Breaking Ground: Women in California Clay (September 10, 2022–March 12, 2023). The Williamson Gallery then acquired this piece. Crystal kindly met with me over Zoom and we discussed her rural California hometown, love of Bernini, and how she remains optimistic in the face of climate change.

Cecelia Blum:I know you’ve been working with clay for some time now, since you got your BFA in 2006. I’m curious what brought you to the medium of ceramics.

Crystal Morey: I actually started as being interested in drawing and painting, just a really early interest, I can’t remember when. I’ve always been interested in realism, gesture, and movement. At a certain point I took a ceramics class and realized that what I was really loving in the way that paint would move, I could pick up in clay. I’ve also had an interest in the figure, and I realized that when I started to work with clay, I could create something that was three dimensional and really figure out how anatomy works in a three dimensional way. So at first it was more of a formal interest, and over time I switched from like “Oh instead of clay just being a way to understand the world, I actually want to make objects that are my art out of it.” And so I switched. I mean I still draw, and I still paint. I would say that ceramics and specifically porcelain have become my medium of choice, at least right now.

CB: Did you always know you wanted to be an artist?

CM: It’s interesting to think about because I grew up in a rural community in Northern California, where the idea of a career was not the cultural norm. Everyone had their passions, but there were very few adults that I knew who had careers that they went to school for. I think in a certain way that gave me freedom. I wasn’t thinking about what I wanted to do as a career, just what I wanted to do as a passion. It just naturally fell into place, I was either going to go into Arts or Women’s Studies, that was my direction. And I decided to go to art school and it just happened in that way. And looking back I see that there are lots of things that anyone could be good at doing, but for me there was not a way to be visual without doing art, so it naturally fell into place.

CB: Do you have a favorite artist or piece of artwork? It can be your favorite at the moment, or just something or someone that generally inspires you.

CM: I love art historical work, I love Bernini, I love Boucher. In terms of the contemporary, I love Kiki Smith, Lisa Yuskavage, and John Currin. As far as a particular piece, I love Kiki Smith’s Lilith. It’s a bronze figure that goes up on the wall, and instead of a traditional figure that’s accepting gaze, she’s looking away from the viewer, towards the wall. It just has a really strong presence that I just really love. It’s such a simple piece, yet so strong. And then Lisa Yuskavage, her work has always spoken to me. It also has a feminist slant that’s embracing a lot of different identities, different kinds of bodies, and un-anatomical bodies which I really love and appreciate. They’re kind of funny, but also serious. I love her work. I also love the artist Patricia Piccini, and I think her piece Young Family is one of my favorites. It’s a humanoid maternal figure with little baby figures. The idea behind this sculpture is that the creatures are human-created, genetically modified hybrids, with a purpose of helping humans. In their created purpose, I see them as being in an incredibly vulnerable position, at the whims of human needs, showing us and warning us of where our species could end up with the abilities of genetic modification.

CB: How did you develop a connection to the natural world?

CM: I think that my connection to nature has changed over time. I grew up in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Northern California, which at first glance is really idyllic. There are beautiful forests and lakes and rivers and streams. Growing up, I didn’t give the landscape a second thought, or think much more beyond its beauty. I just enjoyed being part of that landscape. And I think as I’ve matured and gotten older, I now live in the San Francisco Bay Area, and my perspective on nature has changed. I think about where I grew up and all of the changes it has gone through. It was historically a gold country, and during the 1860s and 70s there was lots of hydraulic mining, which washed away the mountainsides and created all kinds of devastation that is still felt there today— chemicals in the ground, water issues. So that’s part of where I’ve come from in terms of my understanding of nature. As I’ve gotten older and learned more, I have really become interested in climate change. There’s this book by Elizabeth Kolbert called An Unnatural History, and she talks about our human effects on the entire world, and how we are in a new era, the Anthropocene, which I find incredibly interesting. This new era is the time where humans have shifted the trajectory of the planet. So I think about that, and I think that’s my macro view of nature and how we are part of it and changing it.

CB:What inspired you to create the RePlanting series?

CM: So my work has always been interested in our connection as humans to the natural world. And during 2020 I had a small baby, and we were indoors.There was a period where there were wildfires in Northern California, and one day we woke up, and it was dark. It was dark outside. The sky became orange, and it was this really weird surreal feeling, like “It’s literally dark outside.” There was a high level of smoke particulates blocking the sun. It just felt like “Oh my gosh, I think about climate change all the time and right now it’s right outside my window.” And at the same time I had this little baby I was taking care of, my little baby. I’ve been interested in vulnerable and endangered species as far as animals, but having this little baby just puts things in perspective about the effects that we’re having on the natural world. I thought about how, for privileged people, we don’t feel the effects the way that more vulnerable populations do. So that led me to think about precious things, while also trying to keep optimism alive. I started to think about seeds that are activated by wildfires, things that can come out of pain, trauma, or disaster. The RePlanting series is coming from a place where climate change and its effects on vulnerable creatures feels and is really dire. And even in these complicated times we have to believe there is a way out; through education, innovation, public policy. In the Replanting series, the seeds the creatures carry are all of these ideas, seeds of new plants, seeds of adaptation, seeds of hope for a balanced ecosystem.

CB: How do you cultivate a sense of optimism regarding climate change? Why do you think this optimism is so important?

CM: I feel like it’s so important because if we just say “Well it’s too late, there’s nothing we can do,” it’s like, what is the point of everything? I think I can get in a mindset that feels very overwhelming, and I don’t know what else to do but to keep that optimism. I think about nature and plants and animals and the way that they adapt and change to new environments. It feels like there’s hope in that and that nature will find a way. Hopefully us being part of that whole ecosystem, we can do that too. I think I try and find optimism in that sort of adaptation.

CB: How long do you typically spend on a single piece? Do you work sequentially or on multiple pieces at once?

CM:So I usually work on multiple pieces, anywhere from two to five at once. I hand build everything. Typically lots of porcelain work is split-cast, but I hand build everything, which makes the drying process really slow. I start from the bottom and work my way up. The piece that The Williamson Gallery has, Scrub Jay and Deer, I built the bottom, and let it dry out slowly, so it creates strength. And then I built the next figure, and the next figure. It’s kind of rough at that point, and I will add and subtract to bring in layers of detail. So from start to finish, it’s probably four to six months per piece.

CB: I noticed all of the human hands in your RePlanting series are oversized and have very long fingers. Tell me more about this choice.

CM: I love hands. I think of them as how we do things in the world, and how we make changes, take care of ourselves, take care of others. I also think of them as visual guides, and I like to think about them compositionally. I think there’s an importance and weight in the gesture of hands. So the hands on my pieces are probably double the size of anatomical hands. I use them compositionally to connect the elements, to connect the figure with an animal or a plant, just to remind us of that connection or of the importance of that. I think hands have a whimsy to them that feels a little otherworldly and magical.

CB: How do you think feminism and environmentalism intersect?

CM: I think feminism is the ability for everyone to have choice and opportunity. No matter your background, where you’re from, your race, ethnicity, religion, just opportunity for everyone. As the world shifts, as the climate shifts, there are opportunities that more people have that other people don’t. I think there’s privilege in where you live and how the climate has been affected. I think of environmentalism as an extension of intersectional feminism. I can’t uncouple the two.

CB: I know earlier you cited Bernini as an inspiration, and I can see how Bernini-esque the female bodies in your pieces feel. Can you talk more about which bodies inspire the ones in this collection?

CM: I love Bernini, and am deeply influenced by renaissance painting and sculpture in general. I find the interest and use of anatomy and composition of this time period fascinating, how bodies are used to convey emotion while sometimes disregarding anatomical size of correctness for visual impact.

I’m also aware that renaissance works were mostly made by men for men in mind. I keep this in mind and try to create from a different perspective, not wanting to continue the idea of the male gaze on a woman’s bodies. As an artist, I am continually rethinking the responsibility of using bodies in my sculptures. All of my figures are femme- presenting, but I don’t necessarily think of them as gendered, I think of them as being a stand-in for humanity. Lately I’ve been interested in bringing in more gestures, more weight, more evidence of life in their bodies— more folds, more volume. I take visual reference from many sources, art historic, inclusive models and dancers, fashion design, and my own body. I often try to internalize what I am saying in a sculpture and then sit in the position, see what it feels like. I reference my own body, but none of the figures are anatomically correct, and a lot of them have changed in order to make the composition more effective, and to bring in an element of contortion or stress or immediacy.

CB: You talk about building your sculptures from the ground up one section at a time. There’s always an emotional or personal aspect to creating a sculpture and seeing it as a fully realized three dimensional object. I would imagine those feelings are especially strong when you’re sculpting a living being, especially a living being that hasn’t existed in the world before. I was wondering how that feels, and what that emotional experience is, of creating ‘life’ in this way.

CM: I always have a vision of what I want to make, and I never end up where I thought I was going to end up. I think I go through different stages. The beginning is always a struggle, and I’m usually not as excited about what I’m making. It’s just labor, building out what I’m going to make. If I come into the detailing portion— like adding leaves, or tiny garbage, or shells, or fur, or making hands— I feel like I’ll fall in love with the sculpture and get really excited. I’ll feel emotion and care for the sculpture. And then there’s the firing process, which is just brutal. Getting a sculpture into the kiln is kind of traumatic, there’s no other way to explain it. When the clay is wet it’s super malleable, and when it starts to dry out it gets really vulnerable to breaking and cracking. Once it goes in the kiln, there’s just a bit of anxiety. It’s hard to know what’s going to happen in the firing process. My clay shrinks twenty percent and the kiln goes up to 2300 degrees fahrenheit, which is a lot of stress for the clay, so it moves around. So it’s tough, you put all of this time—several months— into a sculpture, and you just have to let go. It goes in the kiln and it’s out of your control at that point. When they come out, I feel like I’m usually still in love with them, maybe a little bit relieved that they survived

CB: Do you see this series (RePlanting) as belonging to a larger artistic movement at all?

CM: The way that I see it, I’m connecting to art history and the history of the porcelain figurine. So I think about that formally, in how the work looks, and the history of porcelain. It’s also connected to marble sculpture and Renaissance painting. It’s not just visually appealing, there’s a contemporary slant that is environmental, and there’s subversive content that makes it go beyond being decorative. I think that there is a larger movement, there are a lot of artists working in that way right now. They use something familiar to bring in the viewer, and then bring in new content to make it relevant and important, and make it questioning or challenging in a different way.

CB: Do you see yourself continuing with your current series/style?

CM: It’s hard to say, but probably. I move really slowly through different themes. I can’t see myself moving away from the theme of climate change, and how humans affect our environment. That feels pretty core to me. I would love to see my work evolve in size. A big thing for me recently has been recreating little elements from the bay, like little shells and mollusks, or even single use plastics and garbage. I would love to make a coral reef figure, so it would be very exciting to me to make something a bit larger.

CB: How does your geographical location affect your artistic practice?

CM: Where I came from felt very untouched by humans, but really the land was devastated. But nature had taken it back, and regrown over the wounds that were created. Right now I live in Oakland, and it’s really urban here. There’s lots of cement, there’s lots of noise. It feels very controlled and affected by humans. Still there are little enclaves of the natural environment that continue to grow. I try to spend time outside of the Bay Area, like in the Redwoods, or at the ocean, and I think that affects the way that I work. Politically, being in a pretty progressive place helps to validate my ideas on climate change and human rights and feminism and free speech.

CB: Those were all of my questions, but do you have anything else you’d like to add?

CM: I don’t know if you have a description of Scrub Jay and Deer, but I wanted to give an explanation on that piece. There’s a scrub jay human hybrid at the top, a mule deer with antlers that are growing acorns, and then at the bottom, there is what I think of as a dump, dirt is filled with garbage and human castaways. The base is the human component of what we have created, and the deer represents what can grow, adapt and thrive even in devastation. I was thinking about scrub-jays, birds that bore holes into dry pine trees that have died from beetle death, which is becoming more common with climate change. They eat the beetles while also boring holes in the pine tree, taking seeds to insert in the holes of the tree, saving them for a later date. There is an entire ecosystem that is created, as the tree is no longer growing, it becomes a food source for the scrub jay, and a place to hold provisions for the winter.

CB: Do you have advice for anyone who is studying the arts right now or thinking about becoming an artist?

CM: Follow whatever makes you excited, and continue to learn. Art history is such a good place to grow. Not necessarily western art history, whatever kind of art history fits your background, your culture, or your interests.

My advice for being an artist is to find community. For me that’s been huge. It’s been helpful to find friends who are artists, that have similar interests and ways of making. I have also found community around galleries where I connect with the programming and work that is shown. Artist residencies, long or short, are another way to keep being engaged. Being an artist in school, the infrastructure is there. And then once you leave school, it’s really hard to continue that. Being an artist can be isolating since we spend a lot of time in the studio. So friends and community are really important, motivating, reminding me that we are all part of a movement and larger artistic purpose.

-Interview by Ludwick Campus Preservation Intern Cecelia Blum ’24 with Crystal Morey, Summer 2023