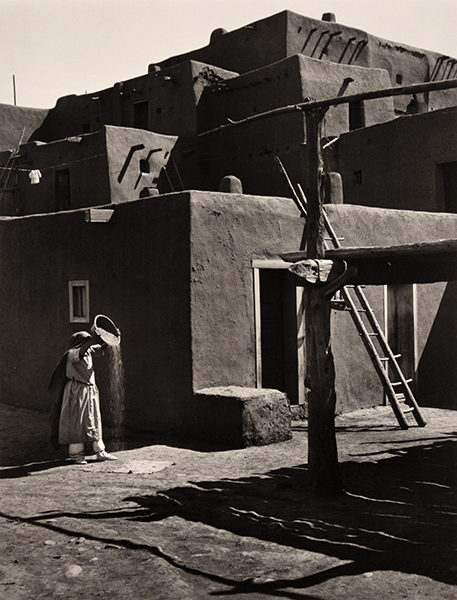

Adams’s photograph, Winnowing Grain, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, accentuates the sculptural qualities of adobe building: the pueblo’s layered cubic forms, and its deeply shadowed doors and windows. The photograph encourages the viewer’s eye to trace the network of ladders running up through the pueblo’s stories. The brightest point of the photograph, however, is the stream of sunlit chaff spilling from the woman’s basket.

She is winnowing grain, that is, separating chaff from threshed grain by tilting and shaking her grain-filled basket and allowing the wind to blow the chaff away. As cultures worldwide have winnowed grain since the beginning of agriculture, Adams’s photograph documents something ancient and eternal in the heritage of the American West. At the same time, by including domestic details such as a child’s shirt drying on a line, Adams also archives a moment of this woman’s everyday life. Indeed, this photograph seems to show the ordinary world overlapping with something eternal.

Adams’s interest in Taos Pueblo is part of a larger Modernist interest in ancient cultures. Carl Jung came to Taos in 1925 on a quest to uncover authentic early cultures surviving into the Modern period. There, he talked with the chief of the pueblo and “learned how all life flowed from the mountain by way of the river, and how God, the sun, needed the assistance of his people in order for the stability of the cosmos to be maintained.[1] Indeed, pueblo chief Antonio Mirabal told Jung: ”We are a people who live on the roof of the world; we are the sons of the Father Sun, and with our religion we daily help our father to go across the sky. We do this not only for ourselves but for the whole world.”[2] Documenting the ancient practices of Taos Pueblo, Adams seems to be following in Jung’s footsteps and participating in the intellectual discussions of his period.