Banner designed by Cecelia Blum SC ’24

Banner designed by Cecelia Blum SC ’24Kieko Fukazawa uses clay to fuse ancient craftsmanship with contemporary commentary. Her recent series, Peacemaker, uses delicate porcelain to pay homage to the many victims of senseless gun violence in the United States. In this interview, she shares her thoughts on the universality of social issues, her upbringing in Japan, and what it means to enact change through art.

Cecelia Blum: You describe yourself as a community-based artist. Tell me more about what that label means to you.

Keiko Fukazawa: I believe art should define its era and reflect what we are living through. My recent works have become more and more political and engage with what is happening in contemporary America politically, culturally, and socially. My work has increasingly grown to involve, reflect, and engage with people’s everyday matters and concerns because my concerns are the same as everybody else’s concerns. Showing my artworks in community-oriented spaces such as non-profit organizations, cultural centers, and university galleries exposes my work to more diverse audiences so that together, we can have meaningful conversations, raise awareness and build connection, as we celebrate diversity, tolerance, and freedom of expression.

CB: Why do you use porcelain in your Peacemaker series? How do you think this medium amplifies the message of these pieces?

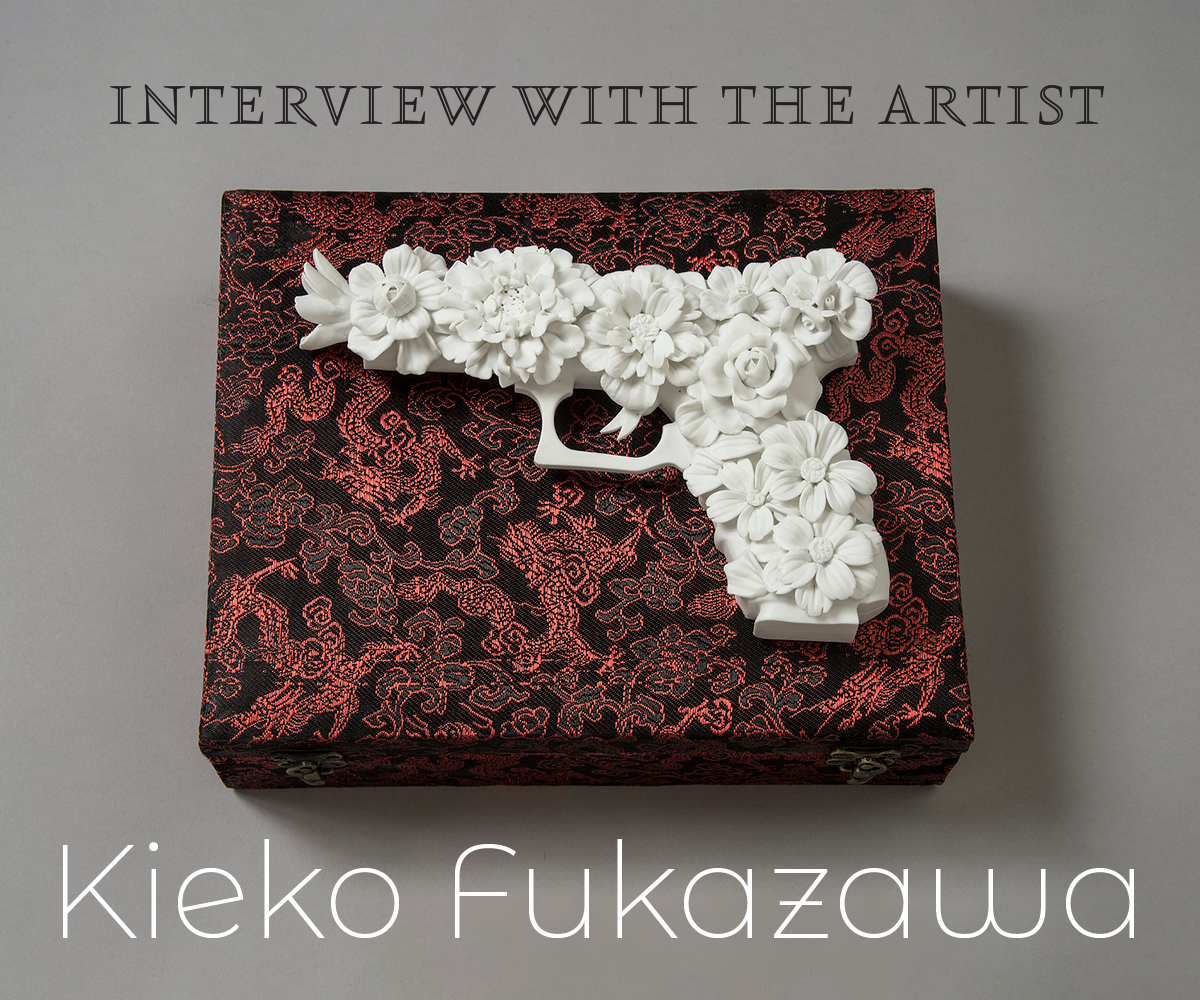

KF: Porcelain provides the most pure white color in clay and is both a very fragile material and yet hard at the same time. These characteristics accurately reflect the subject I am dealing with: gun violence and mass shootings in America.

White is the color of death and mourning in Japan, as it is in most East Asian cultures, and the boxes I use to display the guns are symbolic coffins. These choices all represent the mournful state of mind that haunts the many communities who continue to feel the lasting effects of gun violence. White also symbolizes purification of hideous events. The flowers, which cover each weapon, remind us of life, instead of death.

CB: You cite your mom as the reason you are an artist today. Was there anything she said or did in particular that stays with you as a motivation for being an artist?

KF:My mother encouraged me to leave home to become an apprentice at Shigaraki, one of Japan’s Six Ancient Kilns and pottery producing sites near Kyoto, while she was battling cancer in Tokyo. I had this once-in-a-life time opportunity to further my craft, but was reluctant to leave because it was 300 miles away and she was terminally ill. She, however, convinced me to pursue my dreams. I remember her saying, “if you were a professional performer, you have to be on stage, and the show must go on, even if your parents die.” She had a very strong spirit, and wanted to be an artist herself. I think she saw herself in me.

CB: You’ve lived in the Los Angeles area since the 1980s. How do you think living in this area influences your work?

KF: I believe that big cities like L.A. serve as a vibrant gateway, with constant and continual flows of new immigrants arriving with their distinct cultural flavors. There is not only one particular tradition or custom to follow in Los Angeles, there are many. At its best, this kind of environment makes newcomers feel welcome, especially in the art world. I really believe California has good soil for germinating all kinds of innovative art. Today, my work reflects what I’ve come to think of as having a Californian outlook, including diverse cultural hybrids with an “anything goes” attitude.

Moreover, traveling from home in Los Angeles to my recent residencies in Jingdezhen, China (known as the “porcelain capital” of the world), has also given me an innovative perspective, platform, and space to experiment with conceptual art that speaks to social and political issues spreading throughout America. This allows me to process domestic issues from a distance while also finding connections internationally.

Living in L.A., going to Japan, and visiting China, these experiences all affect how I work with clay to highlight ceramic artistry, process, and history in order to demonstrate the medium as a worthy material and art form that vividly speaks and breaks boundaries.

CB: Did you use a real gun to create the molds used in this collection? What was the emotional experience of working closely with the mold of a gun, a shape that carries so much political and emotional weight in this context?

KF: To my surprise, my tech assistant found the CAD (Computer Aided Design) files of the Glock 17 and AR-15 available for purchase online, which are the most-used handguns and rifles in mass shootings and gun violence from the past 20 years in America. You can easily buy these detailed drawings from the internet, so I did. I then used a 3D printer to make originals in plastic applying the CAD file, before making a mold. This also means that anybody with access to the Internet can easily make realistic-looking plastic guns and rifles without any restrictions, which is a problem.

After I make an original in plastic, I then make a plaster mold from the plastic original, and the guns can then be cast in white porcelain and reproduced on a larger scale. For my earlier standalone pieces in the Peacemaker series, I honored mass shooting victims by covering the casted handguns and rifles with white porcelain flowers. These flowers are the state flowers of where these mass shootings occurred, and the more recent pieces have each state flower representing the number of victims who died in each shooting.

CB: Do you maintain hope that things will change in America regarding gun violence? If so, how do you maintain this hope?

KF: Unfortunately, I remain motivated by what are now daily mass shootings or instances of gun violence that I hear about through NPR and other news media. Sad to say, my anti- gun violence work is very timely and relevant. I constantly feel like before I can grasp the enormity of the current shooting, another one has already occurred. People are getting numb to it. I feel a strong sense of urgency to get my anti-gun violence work out there faster and to a wider audience, to make it more provocative, clearer, and stronger, and to exhibit these pieces in as many places as possible.

By sharing the Peacemaker series along with the installation piece like 9/365 Days in as many venues as possible within the Los Angeles area and beyond, my goals are to inform people of this astonishing rate of gun violence and preventable death in America. The project will involve communities working together to raise awareness and build connection as we celebrate diversity, tolerance and freedom of expression. And by participating in exhibits and working directly with local communities, I hope to spark meaningful dialogue, empower people, and affect change. I hope to give us a way to recognize and honor our connections so that we can collectively find solutions to these pressing issues that affect us all.

CB: The flower motif is prevalent in many of your pieces, including your Made in China series and your Homage to AW. Flowers are especially central in Peacemaker. What draws you to this symbol? Is there a breed of flower that holds particular significance for you, or one you are especially drawn to?

KF: In the Made in China series, I appropriated Mao’s image in order to comment on his 1955 campaign “Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom,” a metaphor used to supposedly represent the people, where he said his government was open to listening to a hundred different opinions by all kinds of people and intellectuals, only to have them come forward and then later be suppressed, punished, or imprisoned. In this series, the porcelain flowers originally represented the Chinese people.

I also wanted to honor the power of people, the power of artisans, and the power of flowers by putting together abundant numbers of them for pieces like Homage to A.W.

For the Peacemaker series, I used flowers to honor mass shooting victims, covering the casted handguns and rifles with white porcelain flowers. These flowers are the state flowers of where these mass shootings occurred, and the more recent pieces have each state flower representing the number of victims who died in those shootings.

Flowers are symbols of life, freedom, and celebration.

-Interview by Ludwick Campus Preservation Intern Cecelia Blum ’24 with Keiko Fukazawa, Summer 2023