Selected Prints (1960–1972): Woman and Bicycle, Execution, Horse and Rider

Introduction The global art scene in the post-World War II era is filled with new ideas and new forms. An influential trend is abstract expressionism developed by American painters such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning in the 1940s and 1950s. Represented by random paint strokes and splashes created by Pollock, the movement advocates an anti-figurative aesthetic and emphasizes intuitive motions involved in ways of creation. In the postwar era, the art world witnessed the merging of cultural elements and traditional art media. Some American and European artists absorbed elements of traditional and contemporary practices and created unique styles that combined representational and abstract approaches.

The three prints by Nathan Oliveira, Connor Everts, and Marino Marini discussed in this three-part series of essays were created between the years of 1960 and 1972. The works show the artists’ shared interest in combining realism and abstraction. All use biomorphic forms to convey a sense of angst. This recurring motif of bodily distortion is often associated with postwar trauma.

The artists discussed here are active in multifaceted practices including painting and sculpting, yet printmaking has always been an important medium for all of them. On “The Education of the Artist and One Print’s Progress” (1979), Connor Everts said, “One of the marvelous qualities of printmaking is the persistence of memory…. Like a dream, the print keeps taking us back to the same crossroad for yet another chance…. Print is the art of opportunity” (qtd. in Ruby 5).

In this final section of the three-part series, we will consider the work of Marino Marini.

Marino Marini: Horse and Rider

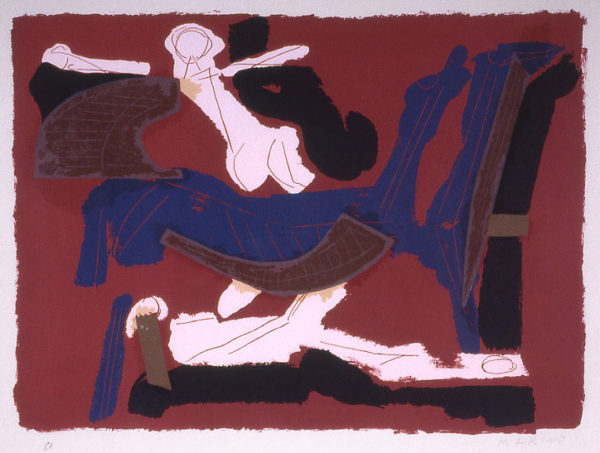

Marino Marini, Italian, 1901-1980, Horse and Rider, 1972, Print,

14 3/8 in. x 19 3/4 in., Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Marino Marini is an Italian sculptor and graphic artist who achieved international success in the post-WWII era. He is famous for his work with the equestrian theme that he consistently dealt with for decades. In his print Horse and Rider (1972), abstract shapes of human and animal forms are interwoven together. The blue shape of a standing horse extends along the horizontal line and separates the rest of the forms. A white human shape on the horse’s back seems to be outstretching both arms as if wrestling with an invisible force. The abstract forms underneath the horse echo the form of the “rider” and appear to be a reflection or a shadow. Although the image is in balanced composition and colors, it nevertheless creates a sense of motion and tension with the contorted biotic shapes. Throughout Marini’s decades-long experimentation with images of the rider and horse, his use of forms underwent tremendous changes. His obsession with the subject matter dates back to 1929 when he was a young art student in Florence. There, Marini spent many hours sketching horse at a local stable (Cutler 20), which served as a basis for his later exploration of the motif. Originally, Marini was interested in depicting harmonious interactions between the horse and rider with representational forms. He shifted the direction of his practice in the 1940s by using increasingly generalized forms in expressive styles. In Horse and Rider, the abstract “horse” holds its neck straight and the head up, as if bearing some kind of pain. The human and animal bodies are fragmented, and their gestures are exaggerated. The unity that existed in his previous work is now replaced by tension and pain. As Marini says, “My equestrian figures are symbols of the anguish that I feel when I survey contemporary events. Little by little, my horses become more restless, their riders less and less able to control them” (qtd. in Cutler 24). A chronological examination of Marini’s work reveals an emotional transformation that the artist went through. Horse and Rider is an example of Marini’s later body of works, and it reflects his struggles with accepting reality and his attempt to capture the bestiality hidden inside humanity. Marini’s practice is also unique due to the use of a common, classical subject in modernist experiments. In multiple ways, Marini finds connections between contemporary issues and the equestrian theme that resonates with him. In a historical context, the connection may be found in refugees who fled Milan on horseback as allied armies invaded in tanks toward the end of the war (Hunter 16); at a more conceptual level, Marini communicates contemporary moods of anxiety and uncertainty by turning a traditional theme into expressive artwork about domination and conflict. For Marini, art is something that transcends arbitrary division of “periods.” He asks, “What is this period of ours about? Speed. This will end one day—a period is nothing when compared with eternity. Eternity, yes, there are things which belong to all periods” (qtd. in Hodin 98). Using the equestrian theme as a carrier, Marini focuses on our connection to a larger social, cultural, and historical context as well as the emotion and struggles that are fundamental to his way of perceiving humanity.

Written by Chenlu (Cindy) Zhu (SC ’19) Wilson Summer Intern 2019

Works Cited

“Connor Everts Biography: Annex Galleries Fine Prints.” The Annex Galleries, www.annexgalleries.com/artists/biography/666/Everts/Connor.

Cummings, Paul. “Interview: Nathan Oliveira Talks with Paul Cummings.” Drawing, 1988, pp. 30–34. Cutler, Ellen B. “Archetype and Allegory: Marino Marini’s Horses and Riders.” Sculpture Review, vol. 55, no. 2, June 2006, pp. 20–25.

Hodin, Joseph Paul. “Marino Marini: Man and Horse, Man and Woman; with French, Italian and German Summaries.” Studio International, vol. 167, Mar. 1964, pp. 94–99.

Hunter, Sam. Marino Marini–the Sculpture. Abrams, 1993.

Martini, Chris. “Nathan Oliveira: Cruising in the Fast Lane.” Studio International, vol. 197, no. 1007, Dec. 1984, pp. 62–63.

Ruby, Kalen. “Variations on a Theme.” Artweek, vol. 15, Dec. 1984, pp. 5–5.

Tooker, Dan. “Nathan Oliveira, Interviewed by Dan Tooker.” Art International, vol. 17, Dec. 1973, pp. 56–57.