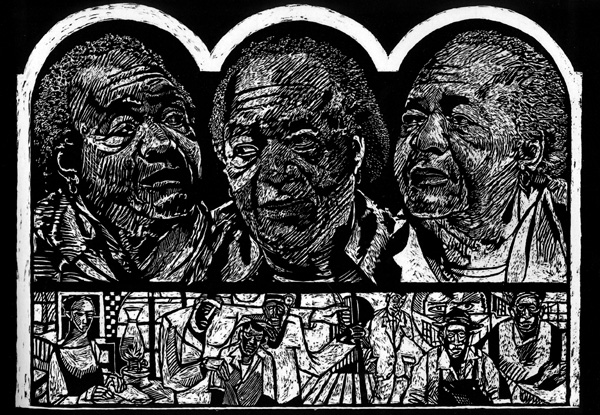

John T. Scott: “Samella Lewis,” 2004

A sort of jack-of-all-trades, the breadth of John T. Scott’s artistic mastery includes drawing, painting, printmaking, and sculpture; his subject matter ranges from self-portraiture to work with important political and social messages. Born John Turrell Scott in the Gentilly section of New Orleans in 1940 and raised in the Lower Ninth Ward, he attributes his first artistic experiences to his parents, learning basic carpentry from his father and embroidery from his mother. Scott continued his artistic education at Xavier University of Louisiana, a historically African American, Roman Catholic university, where he studied under painter Numa Rousseve and sculptor Frank Hayden. As Scott states, “The Vietnam War was an impetus to continue my education,” and so, in 1963 he began his studies at Michigan State University and completed his MFA in 1965. During his time at Michigan State, Scott worked as an assistant to his professors, sculptor Robert Weil and painter/printmaker Charles Pollock (the brother of Jackson Pollock). Scott returned to New Orleans in 1965, to serve as professor of fine arts at his alma mater. He continued to teach for 40 years, fleeing to Houston just before Hurricane Katrina. When asked whether he would return to New Orleans, Scott replied, “That’s the only home I know. I want my bones to be buried there. I belong there. I need New Orleans more than New Orleans needs me.” Scott, who had recently undergone a bilateral lung transplant, died in Houston on September 1, 2007 and never returned to his home town. However, as a vital member of the New Orleans art community, Scott left his mark on the city he so loved with public works, including, “Spirit Gates,” which marks the New Orleans Art Museum entrance and “Riverspirit,” a bas relief aluminum sculpture located on the Port of New Orleans building.

The local traditions of New Orleans, which draw on the African and Caribbean cultures, heavily influence Scott’s work. His Diddlie Bow Series, created between 1983 and 1984, demonstrates this influence. The brass and wooden sculptures are inspired by mythical African ritual and allude to the development of blues music, a cross between African rhythms and western harmonies. His method comes out of an improvisational thinking, which mirrors that of a jazz musician. During his creative process, Scott uses what he calls “jazz thinking” or “spherical thinking,” which enables him to make connections between entities and ideas that may be invisible to others. Perhaps due to its jazz-like construction, Scott’s work often contains movement either kinetic or implied. Many times the movement of a sculpture is communicated in the “self-choreographed movements required by the viewer to fully experience his art.” The desire to invoke movement continues through Scott’s main objective to “move someone’s spirit.”

While Scott attained national recognition during the 1980s, the years between 1992 and 2004 were his most prolific period. In 1992, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation awarded Scott the MacArthur Fellowship, or “genius grant,” given to individuals who demonstrate exceptional creativity in their fields of endeavor. Relatively few artists have received this honor, especially those working in the field of visual arts outside of New York. Although the grant established Scott as one of the most innovative artists in the country, he was humble about the award and the exceptionally generous stipend, with which he built new studio space. Scott commented, “I’m glad somebody thinks I’m a genius, but it hasn’t changed my perception of myself…Coming out of a minority situation, it’s always been important for me to be centered and know what I am. Nobody made me credible except myself…” It is exactly this experience as a minority that Scott’s rich body of work addresses. His art brings attention to the national black arts scene and the political issues surrounding African American life and history. His work, Samella, perfectly demonstrates the pairing of the two subjects.

In Samella, a woodcut series of 80 prints, Scott depicts his friend and fellow native of New Orleans, Samella Lewis. A pioneer of African American art education, Lewis taught at Scripps College as a professor of art history and the humanities between 1968 and 1984. Scott created this print to celebrate Lewis’s 80th birthday. Framing three portraits of Lewis under a triple arch, he presents his longtime friend with both historical importance and intimate closeness. Similar to the movement Scott creates in his sculptures with vibrant colors and exuberant forms, the different angles of Lewis’ head give the print an implied movement that brings the portrait alive. The scenes of African American life below these portraits tie Lewis into a larger African American narrative. This piece speaks to the manner in which Scott incorporates the history and culture of the African American community throughout his work.

References

- Holland Cotter, “John T. Scott, New Orleans Sculptor, Dies at 67,” New York Times (September, 9 2007)

- “Circle Dance: John T. Scott Retrospective, May 7- July 10 2005,” Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Resource Library

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Richard J. Powell, “Circle Dance: The Art of John T. Scott,” Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Resource Library

- Qtd. in Ibid.

- The revenue from the sale of the prints went to a scholarship for the United Negro College Fund.

Written by Megan Downing (SC ’08), 2007-08 Academic Year Wilson Intern.