Exhibition graphic created by Gigi Hume ’23

Star Machine transports viewers to the Golden Age of Hollywood, and questions what makes it glitter. Behind the lights, camera, action—what forces were at work on the women of Hollywood? In a first for a virtual intern exhibition at the Williamson Gallery, 20 loans from other institutions like the Los Angeles Public Library and the Margaret Herrick Library complement five photographs from the Scripps College permanent collection. Through publicity photographs and film stills of prominent 1930s actresses—from Marlene Dietrich to Anna May Wong to Bette Davis—Star Machine explores how the studio system and publicity apparatus manufactured starlets’ compelling, commodifiable personas as viewers move chronologically through the decade.

This exhibition situates viewers in an all-too-recognizable context: a saturated, sensational media landscape, threats of censorship by a vocal minority, and women audiences’ craving for engaging, dimensional representation amidst a landscape of limited reproductive freedom. It’s within this context that actresses were the primary representation of women in movie-making. Meanwhile, industry-imposed barriers like the infamous Production Code censored depictions of violence, sex, and obscenity on-screen, sharply dividing the decade’s movies into pre- and post-Code. Seen through the lens of this exhibition, viewers are encouraged to question how the Code’s strictures shaped and limited how stars could perform their personas. Additionally, and crucially, Star Machine will not shy away from the institutionalized oppression that flattened and marginalized actresses of color, examining how racialized depictions of these women reflected white-centric values.

Jeanine Basinger, a film critic and the author of the eponymous book Star Machine, commented that Old Hollywood stardom was a product of “mathematics and moonlight.” The calculation and luck of studio executives, publicity figures, and individual actresses is central to this exhibition and to the understanding of how stars were made, not born. The stars of this exhibition were made through a combination of submission, subversion, and resistance.

Curated by Gigi Hume SC ‘23, Wilson Arts Administration Summer 2022 Intern

Lupe Velez, 1930s

Core Collection

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences

Lupe Velez and Edward G. Robinson in EAST IS WEST (1930)

Core Collection

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences

Throughout her career, Mexican-American actress Lupe Velez’s (1908-1944) persona was highly racialized in the “feisty Latina” mold. The so-called “Mexican Spitfire” and “Ball-of-Fire Velez” frequently played “ethnic” roles as was the case in the above still from the film East is West (1930), where she dons yellowface to play a Chinese woman. In both her film roles and publicity coverage, Velez’s characterization centered on her flamboyance and “foreignness,” implicit in writers’ use of choice descriptors like “untamed” and phonetic spelling when quoting her. It is now believed that Velez had undiagnosed bipolar disorder. Her manic phases were likely exploited in her film roles and publicity coverage to create a persona in line with the industry’s idea of how a Latin woman behaves.

Dolores del Rio and Joan Blondell Holding WAMPAs Trophy (c. 1931) (printed in 1934)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

In the above image, stars Joan Blondell (left) and Dolores del Rio (right) hold the trophy for the Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers (WAMPAS) Baby Stars promotional campaign. From 1922 to 1934 (excluding 1930 and 1933), studio publicists awarded actresses who they felt were on the brink of stardom. Del Rio charmed as the pined-after vamp in films like Flying Down to Rio (1933) and Wonder Bar (1934) while Blondell wise-cracked in Blonde Crazy (1931) and Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933). Del Rio, a 1926 honoree, and Blondell, a 1931 honoree, each represent the dominant personas for women of the 1930s: the glamor girl and the working-class girl.

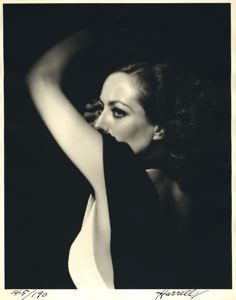

George Hurrell

Joan Crawford (1932), 1981

Scripps College, Gift of the Yarema Family Trust

2006.4.5

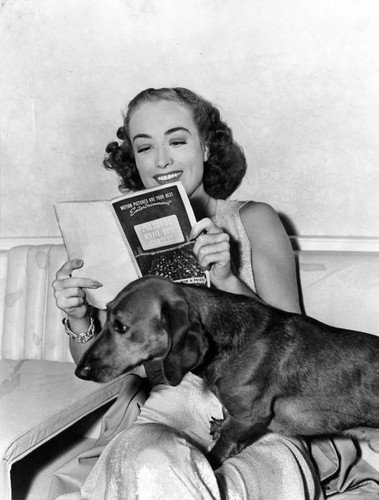

Joan Crawford, movie quiz contestant (1938)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

In the May 1934 issue of Movie Classic, glamor photographer George Hurrell offered this: “I am often asked whom I consider the easiest photographic subject on the screen. I always name Joan Crawford, for you can do almost anything with Joan in front of a camera.” During the height of her career, Crawford (190?-1977) established herself as someone who was devoted to fulfilling the demands of stardom, be it smiling with a movie quiz magazine or sitting for a glamor shot. Her ability to convincingly shift between down-to-earth working girl and otherworldly glamor girl speaks to her remarkable staying power throughout the decade and beyond.

A Code to Govern the Making of Motion and Talking Pictures, 1934 (published 1944), pp. 5-9

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

The Production Code was established in July 1934 following a campaign by the Catholic Church and the Legion of Decency that recruited millions of Americans to pledge not to see “immoral” movies. Fearful of government censorship, the film industry previously established the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) in 1922 to strengthen investor and audience relations. Prior to the enforcement of the 1934 code, Will Hays, the chairman of MPPDA, established “The Formula” in 1924 to prevent the production of “objectionable” material and then a list of “Don’ts and Be Carefuls” in 1927 to prohibit, “profanity, nudity, drug trafficking, and white slavery in films and urged producers to exercise good taste in presenting such adult themes as criminal behavior, sexual relations, and violence.” (Source) With the MPPDA’s establishment of Production Code Administration (PCA) under the strict rule of Catholic layman Joseph Breen, every studio had to submit their scripts to the administration before production to ensure that they didn’t violate the above rules. No film could be distributed without a PCA seal of approval lest they risked a $25,000 fine. The code eventually fell away in 1968, leaving a 34-year legacy of films that extolled conservative values at the expense of nuanced social and political commentary.

United Artists Board (1934)

Security Pacific National Bank Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Though it is more commonplace today for actresses to parlay their on-screen fame into production power, when Mary Pickford (1892-1979) formed United Artists with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks Sr, and D.W. Griffith in 1919, the move was industry-disrupting. Her status as “America’s Sweetheart” in the silent era afforded her the leverage to negotiate the terms of her contract as an actress and dictate artistic and financial decisions as a producer. Following her retirement from acting in 1933, Pickford continued to produce films for the distribution company throughout the 1930s and 1940s. A subversion of the machine, she, as her biographer Scott Eyman put it, “saw herself as a franchise and she demanded more and more and more” (Source).

Alison Skipworth and Bette Davis in DANGEROUS (1935)

Core Collection

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

When asked by an interviewer in the January 1935 issue of Silver Screen how she became the “personification of the gal who made good,” Bette Davis (1908-1989) responded breezily, “Oh that…just hard work.” Davis’s star persona was characterized by a take-no-prisoners ethos, refusing to change her name and pursuing unsympathetic roles. The above still is from her film Dangerous (1935), for which it’s thought she won the first consolation prize Oscar in 1936 after being snubbed for her turn in Of Human Bondage (1934). Speaking to the machinations of the studio system, it was rumored that her home studio, Warner Brothers, refused to launch a 1935 Oscars campaign for Davis because she was loaned out to RKO Pictures for the film. The move exacerbated the contentious relationship between studio and star—the culmination of which came when Warner Brothers won an injunction barring Davis from appearing in any English films. Her vocal resistance to feeling like an “assembly line worker” seemed to complement her headstrong on-screen characters well, endearing her to audiences and igniting what New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther called the “Bette Davis Reclamation Project” (Source).

Publicity photo of Thelma Todd (c. 1934)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Inquest for Thelma Todd (1935)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Garage where Thelma Todd died (1935)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

During her short time in Hollywood, Thelma Todd (1906-1935) was a comedienne and restaurateur known for playing the straight woman with ZaSu Pitts in the duo, Pitts and Todd. Sadly, in 1935 at age 29, she died under suspicious circumstances in a garage above her restaurant. The press coverage that followed speculated wildly about the cause of her death and her frame of mind shortly before she passed. Crowds of people attended her inquest and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner published photos of her body. Hers is an example of how the publicity apparatus was all-too-willing to exploit a star’s name and tragedy in order to craft sensation.

Ted Allan

Jean Harlow (c. 1930s)

Scripps College, Gift of David Fahey

2016.19.3

Clarence Sinclair Bull

Myrna Loy, Clark Gable and Jean Harlow, WIFE VS. SECRETARY (1936)

Scripps College, Gift of David Fahey

2016.19.9

The original “Blonde Bombshell,” Jean Harlow (1911-1937) often played the “modern woman”—a working girl who approached sexuality with openness and good humor. Her performance of that persona markedly shifted in the pre- and post-Production code eras. Prior to 1934, Harlow’s characters in films like Hell’s Angels (1930) and Red-Headed Woman (1932) were more explicitly sexual as “devious” women who tempt the “good” men in their orbit. By 1934, her films verged toward the comedic variety in Libeled Lady (1936) and Wife vs. Secretary (1936), a promotional still for which is featured above. Her vibrant hair color was swapped for a muted “brownette” and frank dialogue was exchanged for marriage proposals. The Production Code, in concert with her desire to be “known for [her] acting, not [her] body” (Source), morphed her screen presence over the course of her short career.

Anna May Wong, a portrait (1937)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Vivacious Luise Rainer (1937)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong (1905-1961) worked throughout the silent era and into the 1930s and 1940s, earning her first lead role at age seventeen in one of the earliest Technicolor films, The Toll of the Sea (1922). The roles she was offered in Hollywood frequently necessitated that she adhere to racialized stereotypes of East Asian women as the “China doll” and “dragon lady,” often supporting a white lead. When a film called The Good Earth (1937)—a story about Chinese farmers in the early 1900s based on the novel by Pearl S. Buck—began casting, Wong fought hard for the role of O-Lan, the self-sacrificing good wife lead. However, when the white actor Paul Muni was cast as O-Lan’s husband, Wong could not be given the role due to the Production Code’s ban on miscegenation, or the depiction of interracial relationships. She was instead offered the role of Lotus Flower, the ill-intentioned concubine, which she refused. The role of O-Lan instead went to German actress Luise Rainer (pictured above) who donned yellowface and won the Best Actress Oscar for 1937.

Ted Allan

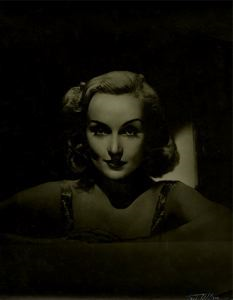

Carole Lombard, n.d.

Gelatin silver print on paper

2016.19.1

Carole Lombard, press agent, props feet on desk (1938)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

In a time when the prevailing personas for women were wealthy glamor girl and wise-cracking working girl, Carole Lombard (1908-1942) seemed to exist in an in-between space. “Personally, I resent being tagged ‘glamour girl.’ It’s such an absurd, extravagant label. It implies so much that I’m not,” remarked Lombard in the January 1937 issue of Picture Play. She charmed as the zany heiress in My Man Godfrey (1936) and the compulsively lying lawyer’s wife in True Confession (1937). To hear film critic Molly Haskell tell it, the world of screwball comedy born in the 1930s—of which Lombard is first lady—is an “elitist world” in that the “charmed couple is cooler, funnier, more beautiful than all the slobs and stooges, the stuffed shirts, and losers who surround them and whose ostensible dullness makes them glitter” (Source).

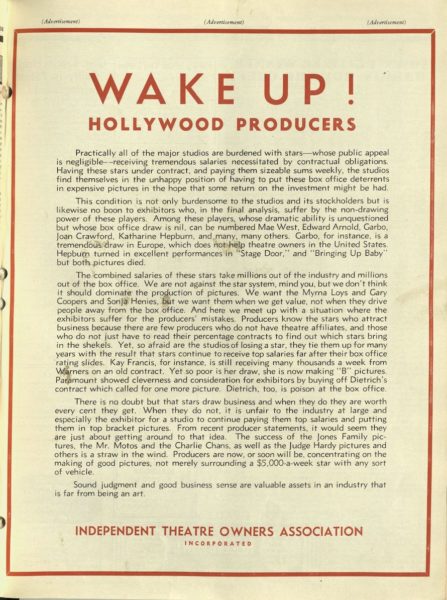

“Wake Up! Hollywood Producers” advertisement, Hollywood Reporter, May 3, 1938 (vol. 45, no. 21), p. 5

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

In the May 3, 1938 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, the Independent Theatre Owners Association released a one-page advertisement calling for Hollywood producers to “WAKE UP!” and recognize the financial burden of performers who were non-drawing, “box office poison.” The ad primarily faults actresses like Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich for the downturn in box office profits. The much-needed and neglected context surrounding the ad is that 1938 was considered Hollywood’s “worst year.”

As Catherine Jurca, author of Hollywood 1938, explains, the industry quarreled about what audiences disliked about the movie-going experience—the “bank nights, double features, B pictures, prestige pictures, bad publicity, and so on ad infinitum.” In the throes of an industry-wide crisis marked by recession, an antitrust lawsuit, and the looming threat of television, no one could seem to answer the question, “What does the public want?” Rather than identifying the systemic issues at play, individual women were convenient scapegoats. At any rate, the box office crisis of 1938 proved to be short-lived. The following year, 1939, is considered Hollywood’s Golden Year, producing some of the most profitable and enduring films of American cinema.

George Hurrell

Marlene Dietrich (1938)

Scripps College, Gift of the Sisters of Browning ’64 in honor of Mary Weis ’64

2015.7.1

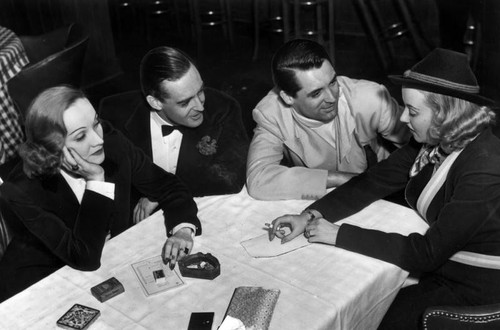

Marlene Dietrich and friends (1937)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

When Marlene Dietrich (1901-1992) came to the United States and was put under contract by Paramount Pictures in 1930, her studio framed her as “their answer to [Greta] Garbo” in that she was a blonde, European, enigmatic glamor girl. Her roles in Morocco (1931) and Blonde Venus (1932) both emphasize her androgynous air; the former film features her initiating one of the first on-screen kisses between two women. In the press, much was made of Dietrich’s choice to wear pants in her everyday life. An entire article in the April 1933 edition of Modern Screen was devoted to answering the question, “Why Dietrich Wears Trousers.” Her queering of the glamor girl persona and her roots in Germany’s Weimar Republic represented a “foreign” intrigue that was leveraged by the star machine. As Dietrich herself put it, “I dress for the image” (Source).

Nina Mae McKinney in GANG SMASHERS (1938)

Toddy Pictures Company photographs

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Nina Mae McKinney (1912-1967) made waves starring in her first film Hallelujah! (1929), the earliest all-sound film with an all-black cast. In the US films that followed, she was often cast in supporting or uncredited roles. As was the case with Anna May Wong and Dolores del Rio, McKinney traveled abroad in the hopes of finding more substantial parts. In Europe, she performed on the club circuit where she was often billed as “The Black Garbo.” She also became the first African American entertainer on British television through the BBC’s experimental broadcasts. When she returned to the US in the late 1930s, she starred in a series of “race films” (Source) with black casts like Gang Smashers (1938), a still from which is featured above. Her role in the film as an undercover agent posing as a cabaret singer showcased her depth and skill as an actress. The remainder of her roles were primarily bit parts as a domestic worker, speaking to the era’s legacy of marginalizing black actresses.

Wardrobe reference for Butterfly McQueen and Hattie McDaniel in GONE WITH THE WIND (1939)

Core Collection

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Hattie McDaniel and Marlene Dietrich in BLONDE VENUS (1932)

Hattie and Sam McDaniel papers

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Hattie McDaniel (1893-1952) and Butterfly McQueen (1911-1995) both entered the film industry in the 1930s playing the “mammy” trope. The mammy featured black women in servitude to white characters as maids and domestic workers—figures that served to perpetuate the myth of the happy enslaved person. McQueen performed the trope in an uncredited part in The Women (1939) as did McDaniel in Blonde Venus (1932) (still shown above) and I’m No Angel (1933). Of these roles, McDaniel offered, tellingly: “I can be a maid for $7 a week or I can play a maid for $700 a week” (Source). Above, McDaniel and McQueen are together in Gone With The Wind (1939), for which McDaniel was the first black performer to win an acting Oscar.

Billie Burke as Glinda the Good Witch (1939)

Courtesy of Mary Bartlett

Billie Burke (1884-1970) spent the bulk of her early career as a star of the stage, not the screen. It wasn’t until her debut as the lead in Peggy (1916) at age thirty-two that she expanded into on-screen work. Throughout the 1930s, Burke played the matron figure, from the comedic social climber in Dinner at Eight (1933) to the kindly, wholesome Glinda the Good Witch in The Wizard of Oz (1939). Growing up in the shadow of the Victorian Era, Burke seemed to function as a bridge between the “Victorian Woman” and the “New Woman.” She at once relished her status as an independent wage earner while extolling the virtues of “never think[ing] of the fact that some day you are going to look old” and “always lett[ing a man] pursue you” (Source). Burke captured that same dichotomy through her characters—at once adhering to the central identities of wife and mother while exploring their potential for individuality and humor.

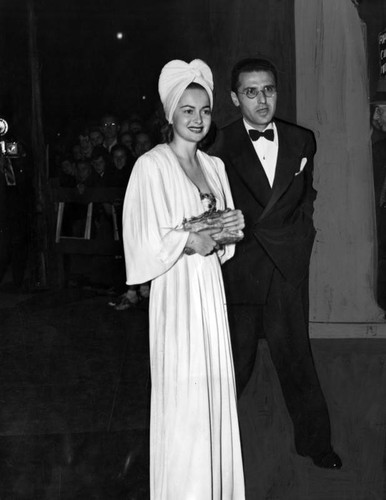

Olivia de Havilland and George Cukor (1939)

Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Pictured above, Olivia de Havilland (1916-2020) and George Cukor (1899-1983) attend the premiere of The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939). De Havilland’s roles in the 1930s were typically morally-upright, “good” women in films like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Gone With The Wind (1939). Similar to her friend Bette Davis, De Havilland grew frustrated with the quality of roles offered by her home studio, Warner Brothers. When she began refusing roles, Warner Brothers suspended her and argued that her suspension period could lengthen her contract dates. De Havilland filed suit against the studio and won in 1945, with the California Supreme Court agreeing that a studio could not arbitrarily extend an actor’s contract. The “De Havilland Law,” as it is known, is still one of the most significant labor wins for the entertainment industry and it was no doubt made possible in part because of the power of her considerable popularity.

George Cukor is known today as the preeminent “woman’s director” and a pioneer of the “woman’s film”—where women are at the center of the film’s universe. However, the distinction of “woman’s director” came with veiled implications about his sexuality. As film critic Farran Smith Nehme opines, “Of course he can direct women, went the argument. He’s gay, that means he’s effeminate, that means he understands women in a way that macho guys never could” (Source). While he never openly claimed the title of “woman’s director,” Cukor imbued depth and complexity into women characters in films like Little Women (1933), Camille (1936), and The Women (1939)—some of the most enduring in the woman’s film subgenre.