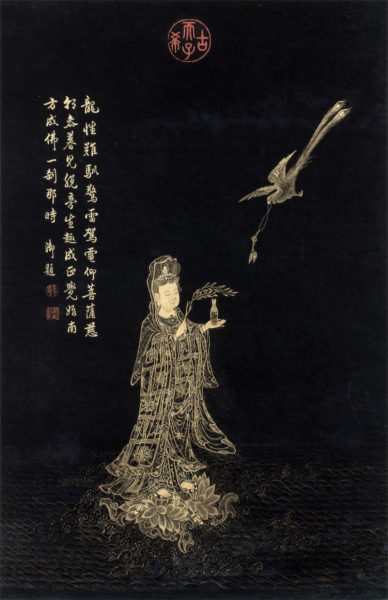

Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion, China, 18th century,

gold ink on indigo-dyed paper mounted as a hanging scroll,

image 25”x16 1/8”, scroll 72×23”; Scripps College, Claremont, CA,

Gift of Dr. William Bacon Pettus, 0322

Guanyin and the Filial Parrot: An Emperor’s Golden Offering

Avalokitesvara, the most compassionate of all the bodhisattvas, is widely revered throughout much of the Buddhist world, and representations of the deity have been painted and sculpted in diverse media for almost 2,000 years. Having vowed to postpone his own enlightenment, or nirvana, until every blade of grass and every grain of sand becomes enlightened, this beloved bodhisattva, or “enlightenment being,” has the ability to search in all directions for suffering souls to save. To aid in his compassionate quest, he assumes a multitude of forms, from a simple princely bodhisattva holding a lotus, to a complex, eleven-headed and multi-armed deity holding an array of spiritually potent objects.

In China, where Avalokitesvara is known as Guanyin, the deity has been painted onto paper, on silk, and temple walls, and has been sculpted in wood, bamboo, bronze, stone, jade, and even porcelain. Typically male but sometimes unmistakably female (with prominent breasts and holding a baby), the Chinese representations of Guanyin vary more than in other cultures. A Buddhist painting in gold on a blue background in the Scripps College collection in Claremont, California, depicts the deity floating over the ocean and gazing up at a bird flying downwards with an offering in its beak. The accompanying inscription, supposedly written by the Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1735-96), makes this uniquely Chinese representation of Avalokitesvara (or Guanyin) all the more intriguing.

Detail of Guanyin, Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion,

Scripps College, Claremont, CA

The scene depicted in this exquisitely rendered painting illustrates the Chinese Buddhist legend of a parrot that became a disciple of Guanyin. According to the tale, a small parrot ventured out to search for its mother’s favorite food (in an act of Confucian filial piety) during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), but was captured by a hunter. The bird managed to escape, but upon returning home discovered that its mother had died. The parrot provided her with a proper funeral — another act of filial devotion — but was consumed with grief. Moved by the parrot’s filial love, Guanyin relieved the parrot’s emotional suffering. The bird became a disciple of Guanyin and offered the deity the gift of a pearl or bead held in its beak.

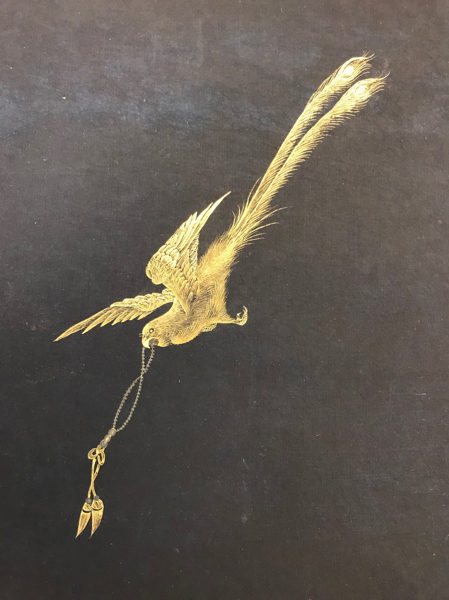

Detail of Parrot, Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion,

Scripps College, Claremont, CA

In this painting, Guanyin is painted floating over the ocean waves supported by a bed of lotuses and greeting the bird as it descends carrying a Buddhist rosary in its beak. The parrot, depicted with the two long tail feathers typical in Chinese images of phoenixes, swoops downwards gracefully with its gaze fixed on the deity. Guanyin, in turn, welcomes the bird with a willow branch and a vase containing pure water (or divine nectar). Guanyin is said to use the willow branch to sprinkle his devotees with the protective and purifying liquid.

Although Chinese images of Guanyin by the sea and holding a vase and willow branch are widespread — in particular in images of Guanyin of the Southern Seas (where the Chinese believed the deity lived) —, depictions of Guanyin and the filial parrot are relatively rare. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has a 17th-century porcelain example and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a stone figure of the pair in that may date to as early as the Song dynasty (960-1279). This particular example is rendered in gold on indigo-dyed paper, a technique typically reserved for Buddhist sacred texts, or sutras, and their frontispiece illustrations.

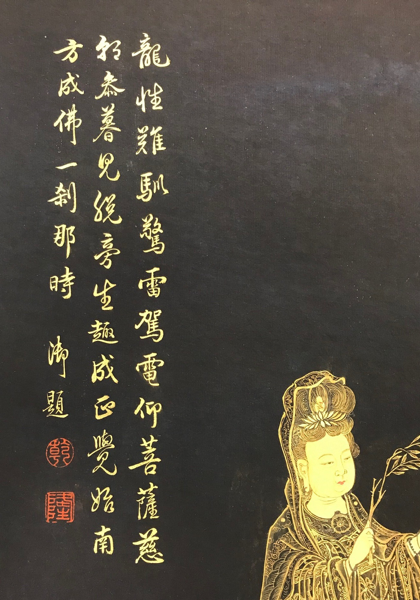

Detail of Calligraphic Inscription, Guanyin, Bodhisattva

of Compassion, Scripps College, Claremont, CA

To the left of the image is an inscription in elegant calligraphy, also in gold pigment. According to a translation by Professor Kathleen M. Ryor of Carleton College of Northfield, Minnesota, the inscription reads:

A dragon [a stubborn nature] nature is difficult to tame

Shocking thunderclaps and flying lightning bolts.

I look up at the bodhisattva’s compassion.

In the morning I worship,

In the evening I discern [the truth] and the certain destiny of the next life. Attaining the source of enlightenment, in the Southern Pure Land [one] becomes a Buddha in an instant.

Inscribed by the Imperial hand.

The inscription is followed by two red seals, the round reading Qian and the square reading Long— seals supposedly belonging to the Qianlong Emperor of China’s Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). At the top of the painting is a large, round, four-character seal that reads Gu Xi Tian Zi, referring to the Emperor as being 70 years old. Although such seals are often problematic and have not yet been confirmed as genuine, it is tempting to consider the possibility that this painting was commissioned (or even painted) by the emperor and then inscribed by him.

The Qianlong Emperor, who lived from 1711 to 1799, was a devout Buddhist who followed the Vajrayana teachings of the Yellow Hat lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. His allegiances to this sect of Buddhism was both political—as his association with the Tibetan lamas helped him legitimize his rule beyond the Chinese heartland — and religious—as Qianlong was also deeply spiritual. In fact, the emperor had himself portrayed in a number of Buddhist paintings as the Buddhist deity Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom and a very central figure in Tibetan Buddhism, seated at the center of the Buddhist Universe —a powerful statement about not only his adoption of the faith but his key place as a chakravartin, or Buddhist universal ruler.

The Qianlong Emperor by Guiseppe Castiglione, China, 1736,

ink, colors and gold on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing.

The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, face painted by Giuseppe Castiglione, mid-18thcentury, ink, color and gold on silk, The Freer Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F200.4

However, despite the fact that he was of Manchu rather than of Han Chinese ethnicity, the Qianlong Emperor also espoused many Chinese Confucian values, and in many ways epitomized the Confucian gentleman scholar, practicing the scholarly arts of poetry, painting, and calligraphy, and was a major collector and patron of traditional Chinese scholarly and other arts. In the 1770s, he sponsored a compilation of Chinese Classics, a project that took 20 years to complete and comprised 36,000 volumes of literature, history, and other documents that helped preserve Chinese Confucian culture. In a highly pious act to honor his own grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor (reigned 1661-1722), the Qianlong Emperor abdicated his throne in 1796 in order to maintain a filial pledge not to reign longer than his grandfather, whose reign had lasted 61 years.

Assuming the painting and calligraphy are genuine, the emperor’s choice of style and subject matter for his painting is fascinating. By using the color palette of the most sacred Buddhist texts, he imbued the image with great spiritual power and preciousness. He may also have been inspired to use gold on blue after seeing the Tibetan thangka paintings of deities rendered in gold on a black ground that were popular in Tibetan Buddhist temples during this period. The subject matter is even more intriguing. According to Dr. Bruce Coats, Professor of Art History at Scripps College, the work may reflect not only his devotion to Buddhist and Confucian teachings but more specifically his devotion to his own mother. When he ascended the throne, his mother, who had been the wife of the Yongzheng Emperor (r.1723-35), became the Dowager Empress Chongqing. He built the Palace of Longevity and Health (Shoukang gong) for her in the capital, granted her unrivalled prestige in his court and took her on some of his inspection tours of the southern part of his empire.

Qianlong often sought his mother’s advice and bestowed upon her many titles, including that of Sage Mother. During the forty years of her life during her son’s reign, her birthday was lavishly celebrated throughout the country. If, according to the large round seal at the top of the painting, the emperor commissioned the painting when he was 70 years old, the work would date to 1781, four years after his mother’s death in 1777 at the great age of 86. Perhaps the Qianlong Emperor, still a devoted son in his old age, felt moved to create this painting with its accompanying inscription in her honor. If so, this fascinating painting of a bodhisattva and a bird is not only important as an accomplished imperial rendition of a Buddhist motif, but also as a touching artistic expression by one of the world’s most successful rulers and greatest patrons of the arts, of his love for his mother.

Detail of large, round four-character seal, Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion,

Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Originally posted on Buddhist Door Global: buddhistdoor.net/features/guanyin-and-the-filial-parrot-an-emperorrsquos-golden-offering