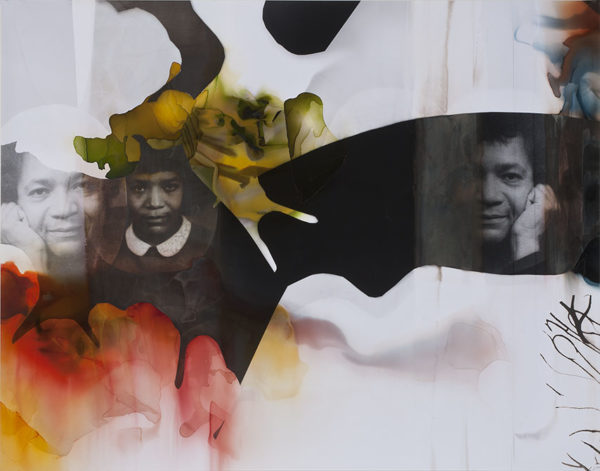

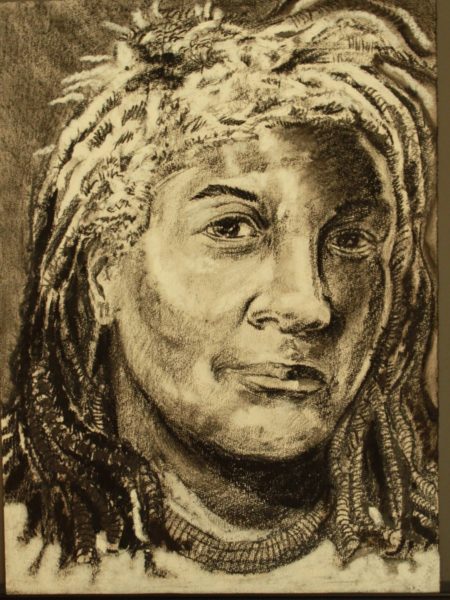

Susan Rankaitis, “Samella (AP) – Samella Lewis, Abstract Painter,” 2011, ink and colors on paper, Scripps College, Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection

“Art is not a luxury as many people think – it is a necessity. It documents history – it helps educate people and stores knowledge for generations to come.”

-Dr. Samella Lewis

All works are part of the Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection, Scripps College

The first Black woman to earn a doctorate in fine art and art history at Ohio State University and the first tenured Black professor at Scripps College (1970-1984) Professor Emerita Dr. Samella Lewis has been at the forefront of promoting Black artists for decades. Among these were many leading female artists whom Samella supported and encouraged.

In 2007, Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Director of the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery, Mary MacNaughton ’70, alumna and artist Alison Saar ’78, and Professor Emerita Susan Rankaitis, created the Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection. The collection was formed in honor of Lewis’ career as an artist, art historian, and educator. This exhibition features works that were either chosen because they are the creation of a Black woman or depict a Black woman—and in some instances, the piece fits into both categories. This exhibition presents pieces created from 1968–2018, encompassing prominent artists from the mid-20th century to emerging artists today. Mentorship is a theme in this exhibition; Elizabeth Catlett taught Samella Lewis at Dillard University, and Samella Lewis taught Alison Saar at Scripps College.

The pieces in this exhibition have a common theme of strength, womanhood, and human agency—with various portrayals of the Black experience emphasizing the importance of compassion and support. I curated the exhibition with this in mind, including labels written by myself, past interns, and Gallery staff members. As a woman outside of the Black community, I chose the title “She Rises” to explore the strength in Black womanhood.

Whether through the creations of Black women or depictions of them, the pieces in this collection reveal to us humanity and hope, while shedding light upon some of the complexities of the Black female experience.

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

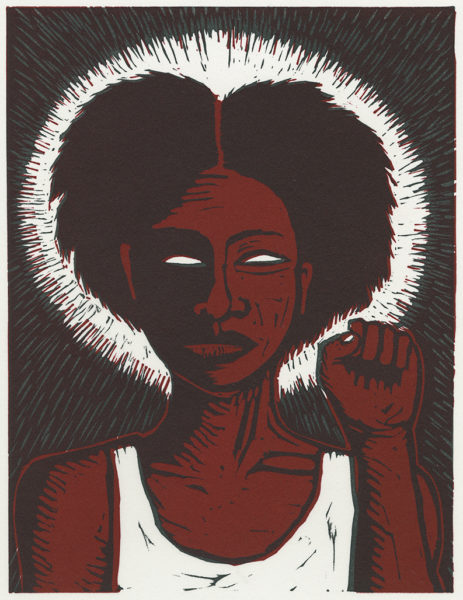

ALISON SAAR, b. 1956

Rise, 2020

2 pass linoleum on letterpress

8 1/2 x 11 in

Scripps College, Purchase, Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection

On July 8, 2020 L.A. Louver Gallery in Venice sent out an email to its mailing list introducing a new print by Alison Saar entitled Rise. The linoleum print depicts a Black woman in a palette of ochre, white, and black holding up a fist in protest. She is determined, powerful, divine even – a quality suggested by the chisel marks that radiate outward from her head like a halo. L.A. Louver, which has represented Saar’s work since 2006, announced that all proceeds from the sale of the 100-print series would be donated by Saar, the gallery, and Leslie Ross-Robertson to local Los Angeles community organizations: Dignity and Power Now (DPN), Summaeverythang Community Center, and Crenshaw Dairy Mart. The print sold out in less than a day, raising $25,000 to support these local Los Angeles community organizations.

Saar was delighted by the response. “I wanted to do something for the Black Lives Matter movement and to help local organizations at this critical time,” explains Saar, “and what I can do is make art.”

Meher McArthur, Gabrielle-Jungels Winkler Curator of Academic Programs and Collections

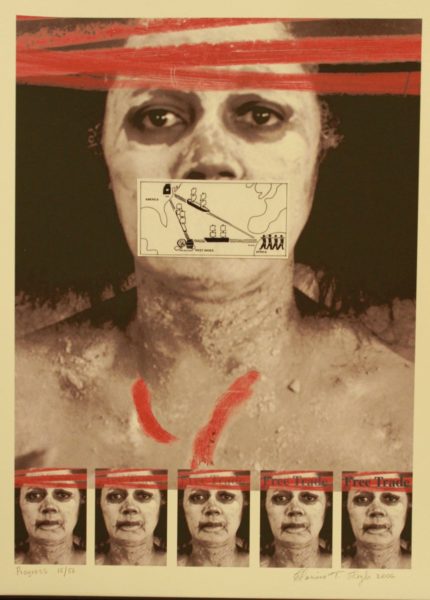

CLARISSA SLIGH, b. 1939

Progress, 2006

Print

16 1/4 in. x 11 7/8 in

2008.9.10

Scripps College, Gift of Samella Lewis

Titled Progress, Clarissa Sligh’s print examines America’s history of racism and trade from a critical perspective. Sligh created this piece in 2006 while living in Philadelphia, following nationwide discussions about free trade in North America. The piece features a large black-and-white photograph of Sligh covered in paint, with a map tracking the Transatlantic Slave Trade taped over her mouth. Beneath the main photograph, a series of identical images of Sligh’s face appear along the border. Red lines are drawn across the top of each portrait, where the words, “Free Trade,” grow in visibility as one gazes from left to right.

The title, Progress, is meant ironically, as Sligh illustrates a lack of change in systemic economic racism and suppression of Black people in America. In a recent statement about the piece, Sligh writes, “I had studied economics in business school and worked in corporate and on Wall Street for a few years so l had learned that ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch,’ which I thought NAFTA was touted as. This was just a continuation of American imperialism. Somebody was going to get the ‘short end’ and somebody was going to make a huge profit.”

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

SAMELLA LEWIS, b. 1924

Child’s Game, 1968

Ink on Paper

25 x 31 in.

2019.24.2

Scripps College, Purchase, Scripps Collectors’ Circle

Samella Lewis’ piece Child’s Game features six figures standing in a circle and holding hands. Lewis limited her woodcut to black-and-white ink, with alternating colored tiles on the floor, and inverted arches that open to a gray sky above.

With clean lines and sharp value contrasts, the woodcut uses geometric shapes to emphasize six characters, with two figures looking down at the floor and one central figure looking straight at the viewer. Lewis captures a sense of movement in her piece, with the group holding hands as if in a dance or game. Through the simplicity of the color scheme and shapes, the work showcases human connection through the figures’ physicality. Created in the middle of the Cold War and the start of the Vietnam War, it is possible Lewis wanted to call attention to the necessity of human connection in the midst of political and social turmoil.

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

SAMELLA LEWIS, b. 1924

Migrants, 1968

Ink on paper

22 3/8 x 29 in.

2019.24.1

Scripps College, Purchase, Scripps Collectors’ Circle

In Migrants, Samella Lewis features seven Mexican migrants, depicted in black-and-white and seated on the ground in what appears to be a forest. Lewis’ linocut illustrates the migrants in detail, with the clothing and facial features of each individual emphasized by Lewis’ intricate cuts. Collectively, the expression on their faces is one of discouragement, but each is seemingly isolated in that pain despite the fact that they are united in their migration. One of the female migrants looks straight at the viewer, crossing her arms and glaring.

Lewis created this piece in 1968, shortly after the Bracero Program concluded in the United States. Under this guest-worker program, which lasted from 1942 to 1964, four million Mexican farm workers immigrated to the United States. In an interview with Eric Minh Swenson in 2016, Lewis spoke about the piece. “They were bean pickers in the back of a bus. I really saw these people. And this woman was so majestic, she was ruling the whole thing, and these were personalities that I saw in the back of this bus.”

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

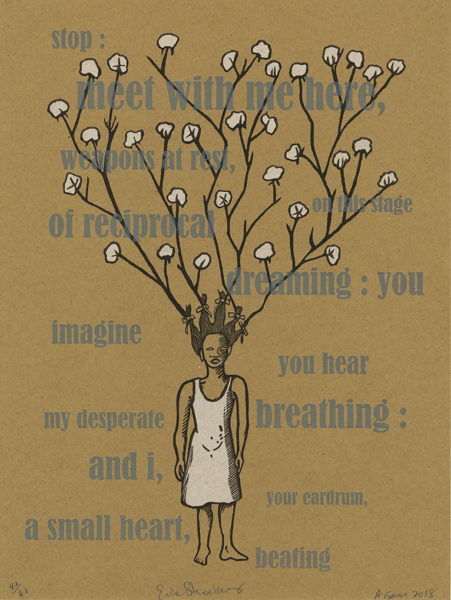

ALISON SAAR (b.1956) AND EVIE SHOCKLEY

Alison and Evie Broadside, 2018

Linoleum and letterpress on Craft Crane paper

16 x 12 in.

Scripps College, Purchase, Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection

In collaboration with Pulitzer Prize nominee Evie Shockley, Scripps College alumna Alison Saar ’78 worked to create a series of drawings for Shockley’s collection of poems, titled “Semiautomatic.” Saar’s works illustrated the section of Shockley’s book titled “the topsy suite,” based on a young female character from Uncle Tom’s Cabin named “Topsy.” This broadside letterpress print is featured in Shockley’s chapter, showcasing Topsy wearing a crown of cotton as words from the poem appear around her.

Saar has worked with the character of Topsy extensively, creating an exhibition titled “Topsy Turvy” in Spring 2018. Describing her collaboration with Shockley, Saar said, “The nature of collaboration between artists and writers is one that everyone should feel comfortable in their own space, and that one person isn’t dictating to the other so it doesn’t become an illustration of someone else’s idea. Because we have such a similar interest and we find a convergence of the wavelength of our ideas, it was an easy thing.”

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

RENÉE STOUT, b. 1958

Play that Number, 2006

Water-based printer’s ink and fluorescent spray paint

18 in. x 13 in.

2008.9.13

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Describing this work, artist Renée Stout stated that she wanted to imitate fliers that fortune tellers often hand out to advertise their service. Stout intended to tell a story of someone who had visited a palm reader and was encouraged to play certain lottery numbers. The piece features a black-and-red advertisement for palm reading on a tan background.

Much of Stout’s work tackles spirituality and Black womanhood. In a recent statement, Stout writes of her palm reader, “My aim was to construct my idea of a fully self-actualized, internally driven woman who was directed by her intuitive connection to the universe and the ability it gave her to serve her community in the narrative I had created surrounding her. She’s beyond victimhood and the need for external ‘approval’ and ‘permission,’ because she’s aware of her own power. The works that I’ve done in this vein are more about wielding a certain kind of spiritual energy and power, and the state that harnessing that kind self-awareness precipitates.”

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

MAYA FREELON ASANTE, b. 1982

Down on War, 2008

Offset Lithograph

37 in. x 24 1/2 in.

2011.9.2

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Asante describes herself as an “artivist,” so much of her work centers on political issues. “The artwork was inspired,” notes Asante, “by my great-grandfather, Allan Freelon, Sr., who was an African American Impressionist painter during the Harlem Renaissance. The image is of Allan Sr., who was drafted during World War I. Allan disapproved of war and suffered a mental breakdown while serving. Once back home he continued creating artwork and his career flourished. I never got a chance to meet him, but I wanted to create a print that honored and exemplified his views about war, freedom, and creativity.”

Skye Olson SC ’13, Wilson Intern 2011

SENGHOR REID, b. 1976

The Ruling Class: Gilda, 2006

Graphite, charcoal, and ink

18 in. x 13 3/4 in.

2008.9.7

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Part of a series of portraits that features four major artists in the Detroit art world, The Ruling Class: Gilda depicts artist Gilda Snowden looking directly at the viewer. Along with the drawing of Snowden in this series, Senghor Reid created images of his mother, Shirley Woodson, as well as Detroit artists Jocelyn Rainey and George N’Namdi. Snowden (1954–2014) was a Black artist and educator from Detroit. Through graphite, charcoal, and ink, Reid captures Snowden’s charismatic facial expression.

In a recent statement about the piece, Reid wrote, “After my mother, Gilda has been my foremost inspiration as an artist, and I am incredibly grateful to have been able to grow up analyzing the work of an amazing visual artist. Being raised and taught by two Black women artists has cultivated within me a unique perspective on the role of art in our society, and how vital art is in the maintenance of a healthy community in a state of continual ascendance.”

Amelie Lee SC ’23, Wilson Arts Administration Intern 2020

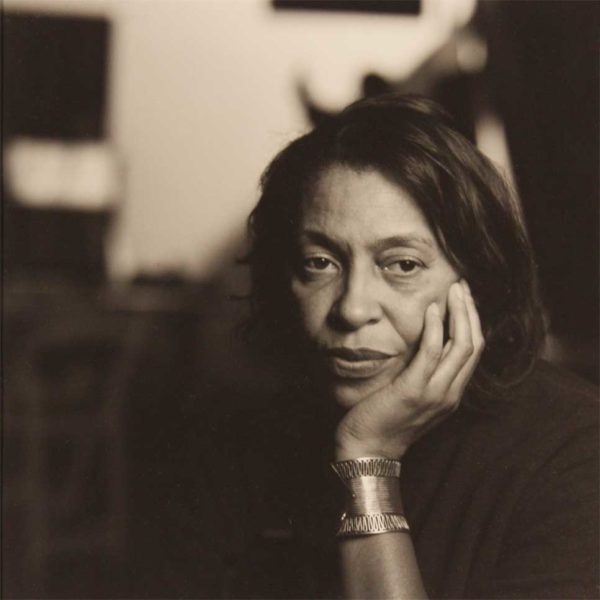

ROBERT HALE, b. 1914

Portrait of Carrie Mae Weems, 2004

Photography, silver gelatin print on Paper

18 x 13 in.

2012.4.11

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Of this photo, the photographer stated:

“I had never met Carrie Mae before this session, but I knew of her work and was a great admirer. I had been on a self-imposed exile in New York at the time, so when I heard through mutual friends that she was working on a project at the Brooklyn Navy Yards, I got her number and called, asking if I could come over to Brooklyn to make a portrait of her. She responded yes, and this image was made in the spring of 2004, on the set inside the recently converted sound stages of the former navy base. She was funny, mischievous, and a willing subject.”

From: African American Visions: Selections from the Samella Lewis Collections catalog, (Scripps College, 2012), p. 57

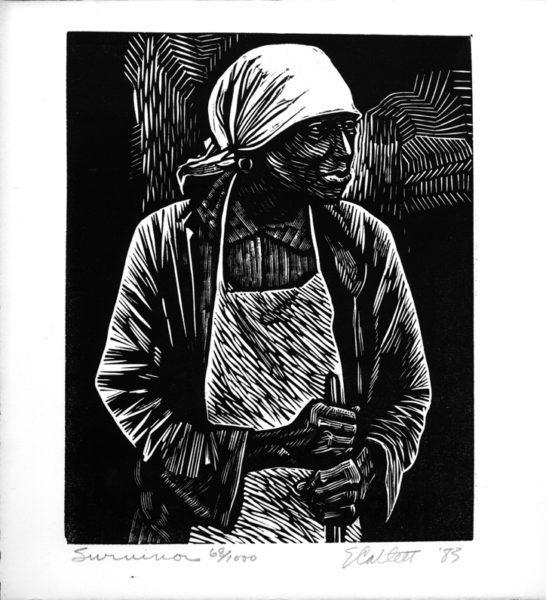

ELIZABETH CATLETT, b. 1915

Survivor, 1983

Print, Ink on paper

9 3/16 in. x 7 3/16 in.

2007.2.1

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Catlett participated in an artistic movement that championed a fresh look at the African American experience and empowered African American viewers with works that would deeply resound in them. As demonstrated in Survivor, one theme that found resonance within Catlett herself was that of the female figure. Catlett employed the image of the African American female to communicate diverse concepts, among them, the heroism and humanity of African Americans. Through the vehicle of her work and her use of it to explore fundamental themes such as mother and child, love, racial injustice and life force, Catlett succeeded in melding the West and Africa, creating a visual vernacular that offers a fuller understanding of the African American experience.

Shayda Amanat SC ’14, Wilson Intern 2012

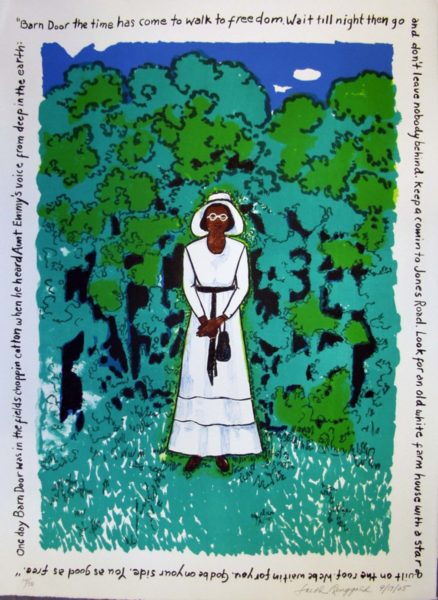

FAITH RINGGOLD, b. 1930

Untitled, 2005

Ink on Paper

30 in. x 22 in.

2007.2.4

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

Beginning in 1999, Ringgold created a series entitled Coming to Jones Road, whose quilts allude to the Underground Railroad and the escape of slaves to the north. Representations of the landscape dominate the quilts. However, in “Coming to Jones Road 3: Aunt Emmy,” the figure of Aunt Emmy fills the canvas, her hands crossed in front of her as she stares directly at the viewer through her wire-rimmed glasses.

The image of Aunt Emmy resurfaces in the ink-on-paper print done by Ringgold in 2005. Portrayed in the same pose, a younger Emmy stares serenely at the viewer, her simple white dress and hat contrasting with the green that encircles her. The text bordering the print reads: “One day Barn Door was in the fields choppin when he heard Aunt Emmy’s voice from deep in the earth: ‘Barn Door the time has come to walk to freedom. Wait till night then go and don’t leave nobody behind. Keep a comin to Jones Road. Look for an old white farm house with a star quilt on the roof. We be waitin for you. God be on your side. You as good as free.’” Typical of her story quilts, the text integrated into the artwork links the image to a larger narrative. Aunt Emmy urges Barn Door to escape slavery and travel to Jones Road. He will be guided not by the North Star, but the star quilt on the white farmhouse’s roof, a reference no doubt to Ringgold’s home. The powerful image of the lone Black woman, a descendant of slaves, surrounded by words of freedom and hope is a testament to the racial and gender discrimination that Ringgold has fought throughout her career.

Megan Downing SC ’08, Wilson Intern 2007-2008

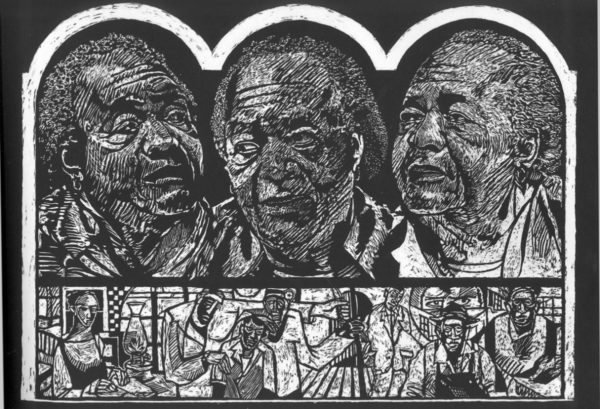

JOHN T. SCOTT (1940 – 2007)

Samella, 2004

Woodcut, Marks: Signed by artist and Samella Lewis, titled, dated, and numbered 57/80 in pencil, lower margin

12 in. x 17 in.

2007.10.1

Scripps College, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop in honor of and in celebration of Dr. Lewis’ lifetime of service to the field

In Samella, a woodcut series of 80 prints, Scott depicts his friend and fellow native of New Orleans, Samella Lewis. A pioneer of African American art education, Lewis taught at Scripps College as a professor of art history and the humanities between 1970 and 1984. Scott created this print to celebrate Lewis’s 80th birthday. Framing three portraits of Lewis under a triple arch, he presents his longtime friend with both historical importance and intimate closeness. Similar to the movement Scott creates in his sculptures with vibrant colors and exuberant forms, the different angles of Lewis’ head give the print an implied movement that brings the portrait alive. The scenes of African American life below these portraits tie Lewis into a larger African American narrative. This piece speaks to the manner in which Scott incorporates the history and culture of the African American community throughout his work.

Megan Downing SC ’08, Academic Year Wilson Intern 2007-2008

Additional Resources:

Alison Saar & Evie Shockley: Conversation and Poetry Reading (2018)

Samella Lewis: Pioneering Visual Artists and Educator, a film by Eric Minh Swenson

MoAD – Full Interview: Samella Lewis on Elizabeth Catlett

To see more works in the collection, visit:

The Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection

To see the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery’s Alison Saar collection, visit: