Children are society’s most impressionable and vulnerable group. How do we raise them? How do we educate them? How do we give them power?

Building the Nation: Children of Edo and Meiji Japan explores how children symbolize collective Japanese identity in woodblock prints from feudal Edo (1603–1868) through the modern Meiji era (1868–1912). Spanning over two hundred years and showcasing prominent Edo and Meiji-era artists including Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858), and Yōshū Chikanobu (1838–1912), Building the Nation focuses on the lives and significance of children in Japan. The show features over twenty Japanese woodblock prints from the Scripps College collection.

During the Edo period, the isolationist Tokugawa Shogunate ruled Japan through a strict social hierarchy. Edo-era society sought to shape children for preordained roles such as warriors, farmers, artisans, or merchants. In 1868, Emperor Meiji’s forces overthrew the weakened feudal shogunate, solidifying Japan as a modernizing nation open to Western influence. Informed by Confucianist, nationalist, and Western thought, childhood became key for the formation of the Japanese citizen. In these works, children move from the shadows to center stage as printmakers altered designs to emphasize their personhood and development.

From playing with bubbles to imperial toy soldiers, these prints reveal the role of children in Japanese society as it evolved from feudal to modern. Education takes many forms in the works. How do we build the children of today?

Building the Nation will be on view at Mount San Antonio Gardens from December 4, 2025 to January 28, 2026. I would like to extend my gratitude to Karen Giles, Jane Park Wells ‘93, the Gallery Exhibits Committee at Mt. San Antonio Gardens, Academic Curator Margalit Monroe and the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery staff.

I would also like to acknowledge the generous contributions of former faculty and visiting lecturers at Scripps College: Professor Emeritus Bruce A. Coats, Japanese art historian Meher McArthur, scholar Dr. Xi Zhang, and current Associate Curator of Japanese Art at LACMA Dr. Rika Hiro. Finally, with deep thanks to current Japanese language faculty members at Pomona College Professor Kyoko Kurita and Professor Peter A. Flueckiger, for illuminating poetic elements in the prints.

Curated by Tara Attanasio ’26, Summer 2025 Getty Marrow Undergraduate Curatorial Intern

Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–94)

Kiyohara no Motosuke

From the book Fashionable Portraits of One Hundred Poets, 1694–5

Woodblock print

Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson

46.1.74

Kiyohara no Motosuke, in the center of this print, was a Heian-period (794–1185) nobleman and poet. Yet Moronobu depicts him as an Edo-period (1603–1868) samurai, illustrating the historic figure in “contemporary” attire and settings. The boy appears to be his attendant. Edo Samurai viewed male children as essential, ensuring a family’s survival within the greater social hierarchy.

Inset poem translated by Kyoko Kurita, Professor of Japanese at Pomona College:

Chigiriki na

katami ni sode wo

shiboritsutsu

sue no matsuyama

nami kosaji to wa

We swore to each other firmly, didn’t we

as we squeezed tears out of our sleeves (a set expression to indicate how much tears were shed)

that it (our love) would never fade away,

just as high waves will never go beyond the pine-tree hill.

* Sue no matsuyama is a set expression used when one wants to indicate eternity.

Ishikawa Toyomasa (1764–81)

October, c. 1770–80

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2016.1.37

Seven boys belonging to the chōnin (merchant and artisan) class dance and blow bubbles in a circle. Inside the house, an older youth offers sake, fish, and good luck charms to a figure of Ebisu, patron deity of fishermen, tradesmen, and merchants. Multiple festivals are held in Ebisu’s honor during Kaminazuki (month of the gods, which occurs in October). Toyomasa’s focus on the exterior children is noteworthy. Edo society usually deemed children’s play as insignificant for documentation. In this print, Toyomasa considers Edo children’s participation in celebrating and preserving traditions.

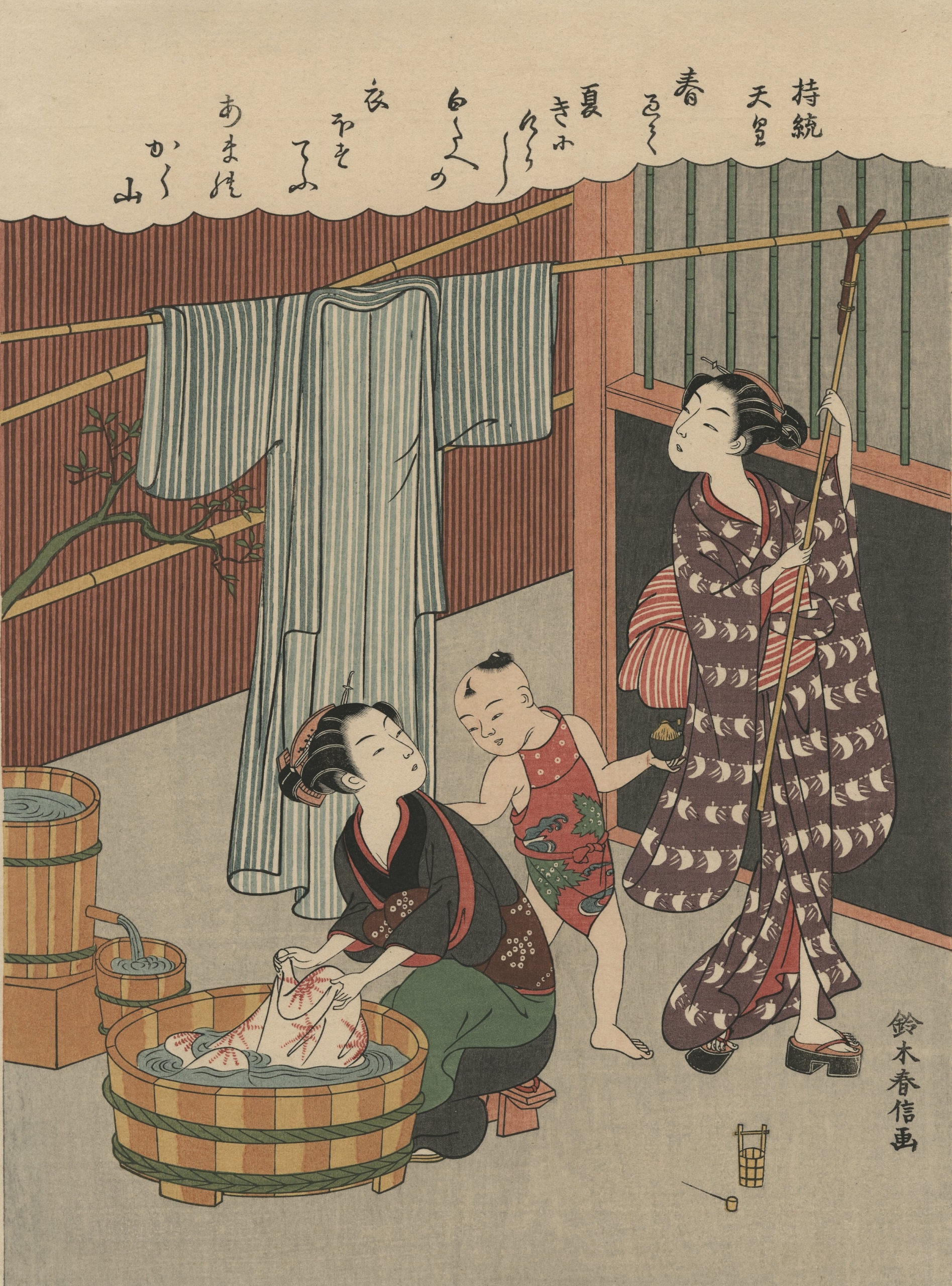

Suzuki Harunobu (1724–70)

Washing, c. 1900

From the series One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2018.1.21

Two women partake in domestic tasks. One washes a garment in a bamboo tub. The other adjusts the line for a kimono (robe) hung to dry. Her long, swinging kimono sleeves are a sign that she is unmarried. Thus, it is likely that the woman washing the cloth is the boy’s mother. The child’s shaved head and singular hair tuft reflect popular customs marking a child’s toddler stage. Children were often included in pictures of women to emphasize fertility and innocence: here, Harunobu includes the child with a slightly darker complexion to highlight the women’s porcelain skin, reflecting Edo ideals of beauty.

Kitagawa Utamaro (1754–1806)

Yamauba and Kintarō, c. 1801–3

Reproduction

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for

Japanese Arts and Cultures

2019.1.54

Kintarō suckles his mother’s breast while pinching the other with his hand. Yamauba’s long black hair is unkempt, but her fair skin, delicate facial features, and large breasts emphasize her beauty. Utamaro, famous for his bijinga (portraits of beautiful ladies) and sensual depictions of women, produced roughly forty works focusing on the theme of Yamauba and Kintarō. Yamauba is commonly described as a demonic and unattractive mountain woman; here Utamaro portrays her as an enticing, fertile mother. Kintarō’s red skin signifies his purported lineage to Raijin, the thunder god, and Yamauba’s lover. Utamaro’s focus on Kintarō nursing highlights Yamauba’s role in nurturing a boy who would become a strong, brave, legendary hero, still celebrated today as Japan’s ideal masculine child.

Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Station 1, Nihonbashi, c. 1833–4

From the series Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō

Woodblock print

Gift of Mrs. James W. Johnson

46.1.64

A 4 a.m., men lead a daimyō procession over the Nihonbashi (“Japan bridge”). Fishmongers, dancers, and merchants’ children surround the men. Erected by the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1602, Nihonbashi was the commercial center of Edo (present day Tokyo) and start of the Tōkaidō, a road linking the cities of Edo and Kyoto. In his series Fifty-Three Stations of Tōkaidō, Hiroshige captured the views, villages, and people along this famous coastal route. Here, Hiroshige begins the series’ journey at the bridge to ground the viewer at the landmark of the shogunate’s authority and the growing merchant class’s presence in Edo.

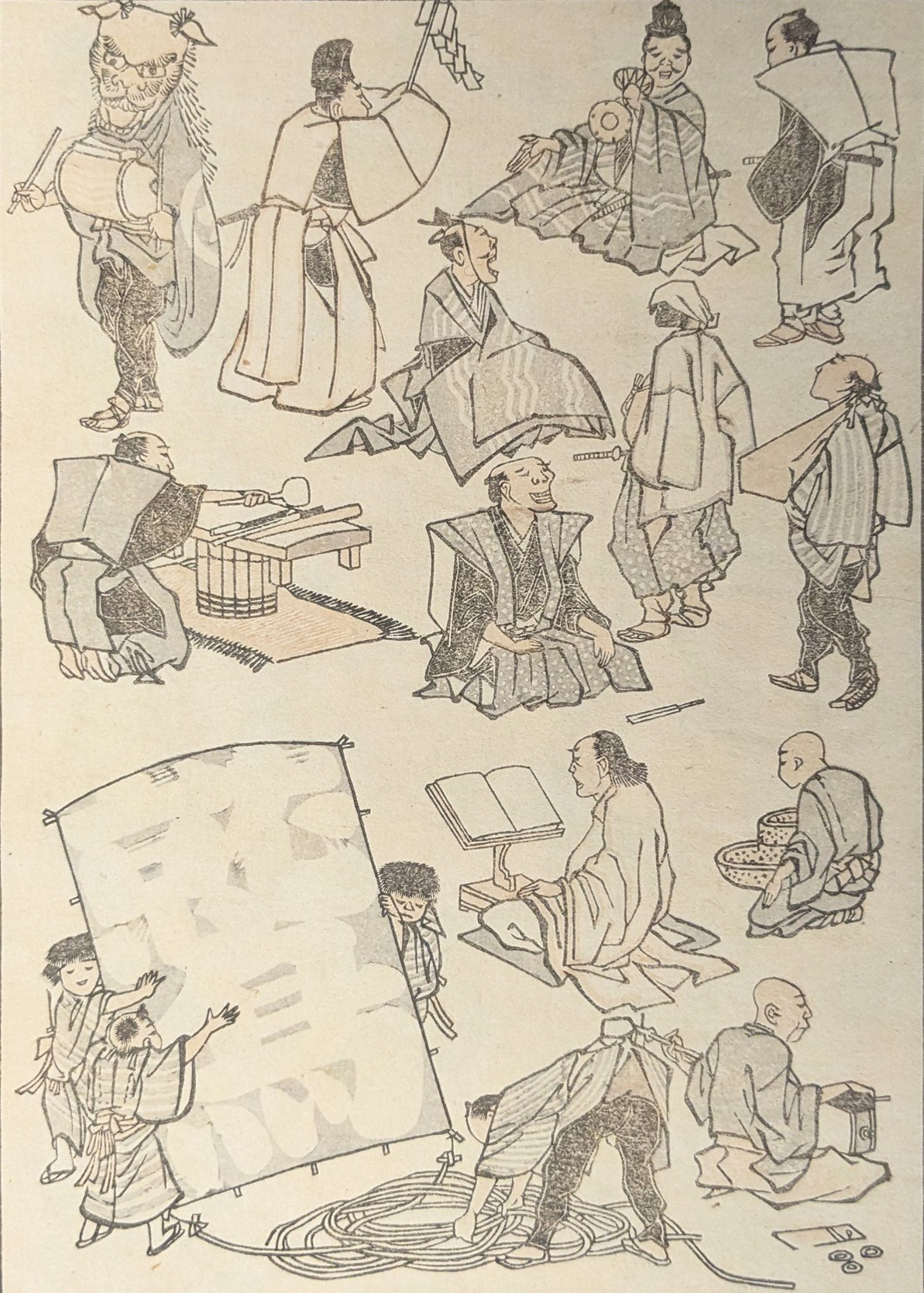

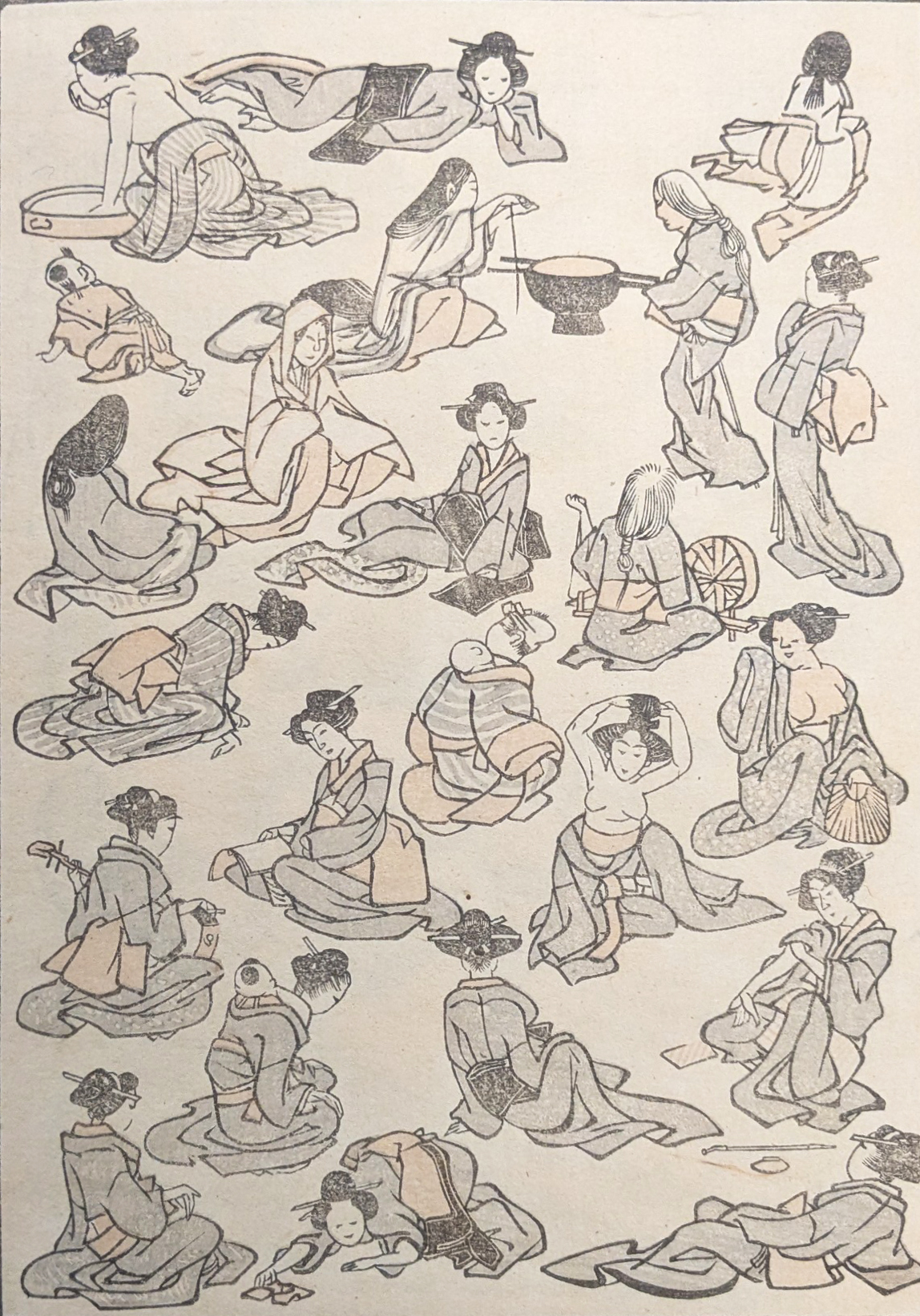

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Hokusai Sketchbooks, Volume 11, 1815

Purchased with the funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2022.1.61

Hokusai is best known for his prints capturing travel and the landscapes of nineteenth-century Edo. He frequently depicted the daily activities of ordinary people interacting with the land and cityscapes. Hokusai also produced ehon, or artist’s books, featuring subjects such as animals, plants, landscapes, and people, as well as supernatural and historical themes. Often referred to as “Hokusai manga” or “manga,” the sketchbooks acted as Hokusai’s drawing manuals for aspiring artists. These ehon feature observations of people ranging from babies to elders partaking in various activities.

Yōshū Chikanobu (1838–1912)

Yamashiro Province, Snow at Fushimi, Lady Tokiwa and Her Sons, Otowaka, Ushiwaka, Imawaka, No. 3, c. 1884

From the series Snow, Moon, Flowers

Woodblock print

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Ballard

93.6.65

Tokiwa Gozen (1138–80), or Lady Tokiwa, was the wife of samurai general Minamoto no Yoshitomo (1123–60). After the Heike clan (led by Taira no Kiyomori [1118–81], depicted in the print’s inset) murdered her husband, Lady Tokiwa fled Kyoto at night with her three sons, fearing that the Heike forces would kill her boys. After wandering in the evening snow and learning of the Heike’s threats to torture and execute her mother, she surrendered to Kiyomori and became his mistress. Her sacrifice spared her son, Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s (1159–89), life. He later became a famous military strategist and Genji warrior, a rival to the Heike.

In this Meiji-era print, Chikanobu recalls events from the Heian period (794–1185). Through his nostalgic retelling of a noble mother’s sacrifice for an important warrior’s survival and development, Chikanobu celebrates and promotes Japan’s classical history during rapid modernization.

Yōshū Chikanobu (1838–1912)

Joys of Reading, 1887

From the series Eastern Customs: Enumerated Blessings

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2004.1.49

A mother and her daughters study in a domestic setting decorated with Japanese furniture and Western materials. Chikanobu emphasizes their engagement with the books and calligraphy. During Meiji-era Japan, western influences shaped the home into an educational space for children. Meiji society stressed the role of the modern mother as the household’s moral manager. She was responsible for shaping her children’s impressionable minds in ways that upheld Japanese morality and identity.

Mizuno Toshikata (1866–1908)

Spring – An Outing In a Field, No. 2

From the series Brocades of the Capital: The Seasons and Their Fashions, 1893

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2006.1.32

A toddler wearing yōfuku (Western-style clothing)—specifically a purple smock—waves her hands at a butterfly. Her older sister and mother, dressed in traditional wafuku (Japanese-style clothing), direct their attention to her. Founded in 1673, Echigoya was a large dry goods store located in the Nihonbashi (recount the earlier print of a bustling bridge) quarter of Edo. In 1893, Echigoya expanded into Mitsui Gofuku (Mitsui Clothing Group). Mitsui commissioned Toshikata to design twelve prints to advertise the group’s Mitsukoshi department stores and promote upcoming fashion trends influenced by Western and Japanese tastes. Department stores became prominent consumption and cultural spaces in developing Tokyo. Mothers brought their children to department stores to witness culture, fashion, and the metropolis’ modernization. Toshikata’s prints reflect the greater cultural contexts pivotal to the child’s development into an informed and influenced Japanese citizen.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Boys and Byobu, 1894

From the series Long Live Japan: 100 Victories, 100 Laughs, 1894–5

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2008.1.38

Three boys and a geisha laugh at an open, animated book. It presents a map of a disrupted coastline with falling ships and abstract, toy-like objects with anthropomorphized features. One child holds a Hinomaru (circle of the sun) fan decorated with Japan’s rising sun emblem. Kiyochika created a series of propaganda prints during the first Sino-Japanese War (August 1894–May 1895); this is the only print in the series featuring children. Kiyochika caricatures the subjects and uses the book as a symbol for the educational systems intended to develop the child’s national identity.

Shoun Yamamoto (1870–1965)

Toy Soldiers, 1906

Woodblock print

Purchased with funds from the Aoki Endowment

for Japanese Arts and Cultures

2012.1.46

Four cherubic boys joyously embrace each other. They encircle the fifth child’s extended offering of wooden toy soldiers bearing pistols. Five noh (classical Japanese theater) masks representing archetypal characters, supernatural creatures, and deities lie on the floor. Yamamoto incorporates a Kyokujitsu-ki (Rising Sun) flag near the child and a Hinomaru (circle of the sun) flag with the toy soldiers, suggesting the normalization of nationalism in childhood from the Meiji era onward.