Ken Heyman (1930–)

Claes Oldenburg, 1965

Gelatin silver print on paper

14 x 11 in.

Gift of Sally Strauss and Andrew E. Tomback

Scripps College, Claremont, CA

When this portrait was taken in 1965, pop art sculptor Claes Oldenburg had yet to design the massive installations—oversized bowling pins, spoons, and ice cream cones—that would characterize his later working career. His irreverence for staid art forms and his inclination toward surrealism, however, were already well established. “I am for an art that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum,” he wrote in a semi-satirical manifesto for a 1961 exhibition catalogue. “I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all.”

During this era, Oldenburg was best known for his radical “soft” sculptures, where he advanced the concept that sculpture did not have to be comprised of hard materials like steel or marble. Their illogical construction subverts expectations and elicits questions regarding the nature and form of art. His Floor Cake, 1962, for example, is a nearly ten feet by five feet piece of cake made of canvas, while his vinyl Soft Pay-Telephone, 1963 sags limply against the wall.

His works are bizarre and comical, a surrealist-inspired vision made tangible. Inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, created out of everyday objects, Oldenburg’s lighthearted pieces rejected the angst and heaviness that abstract expressionism embraced after World War II. His monumental sculptures often reside directly on the floor, for he quite literally intended to take art off its pedestal. According to conservator Sherry Phillips at the Art Gallery of Ontario, early museum visitors would jump on his 1962 Floor Burger because it resembled a beanbag chair. “The only thing that saves the human experience is humor,” Oldenburg has said.

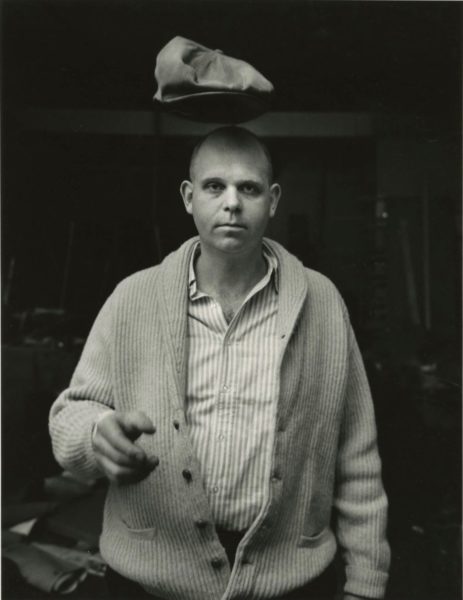

This portrait taken by Ken Heyman taps into a similar whimsicality. Oldenburg appears deceptively serious as he faces the viewer and deadpans into the camera. Yet on closer inspection, one notices that something more is afoot. His right hand is outstretched to throw his newsboy cap—a cap that appears to float above his head in what may be a subtle nod to surrealist painter Réne Magritte’s The Son of Man, 1964. Magritte’s painting features a suited man whose face is obscured by an irrationally suspended apple.

Even though it almost certainly took multiple attempts to capture this image, the visual hat trick appears effortless, as simple and yet as unorthodox as inflating a slice of cake to ten times its normal size. Both Oldenburg’s works and Heyman’s portrait of the artist himself elevate the mundane into something unexpected and playful.

Lauren Koenig ’20, Wilson Intern Summer 2018

Sources

“Claes Oldenburg.” MoMA, The Museum of Modern Art, 2018, www.moma.org/artists/4397.

Clarke, Bill. “Claes Oldenburg: Hold the Pickle?” ARTnews, ARTnews, 4 Apr. 2013, www.artnews.com/2013/04/08/restoring-oldenburg-burge/.

Kennedy, Randy. “Claes Oldenburg Is (Still) Changing What Art Looks Like.” The New York Times, The New York Times Company, 16 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/16/t-magazine/claes-oldenburg.html.

Mumokvienna. Claes Oldenburg: The Sixties. Museum Moderner Kunst Foundation, Vienna, YouTube, 14 Mar. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9mznIVtt-ik.

Oldenburg, Claes. “I Am for an Art: Claes Oldenburg on His 1961 ‘Ode to Possibilities.’” Walker Art Center, Walker Art Center, 20 Sept. 2013, walkerart.org/magazine/claes-oldenburg-i-am-for-an-art-1961.