As an African American woman and artist launching her career in the 1960s, Faith Ringgold fought many battles against racial, gender, and artistic discrimination. Ringgold was born in Harlem on October 8, 1930. She received her BA in Fine Art and Education from the City College of New York in 1955 and then earned an MA from the same institution in 1959. Immediately after graduation she began teaching art in the New York City public schools and continued to teach through 1973. In order to become an artist, Lisa E. Farrington writes in Faith Ringgold: “the first thing she had to do was believe that she, an African American woman, could penetrate the art scene without sacrificing one iota of her blackness, her womanhood, or her humanity.” In her career, Ringgold has preserved her identity creating work that speaks to her experience as a black woman working in a field dominated by white males. Best known for her story quilts, Ringgold has achieved enormous success working predominantly in a medium considered by the traditional art community to be “decorative,” a category inferior to that of “high art.” Ringgold’s work conveys powerful political messages and “chronicles her search for human dignity and empowerment, and her tireless activism against racial and gender discrimination….”

Ringgold is widely known as the author and illustrator of the Caldecott Honor Book, Tar Beach, which tells the story of young Cassie Louise Lightfoot, a character modeled after Ringgold herself, whose family spends the hot summer nights on the rooftop of its Harlem apartment building. Cassie dreams of flying over the city to be free of the hardships her family faces as African Americans in the 1930s. The story is ultimately one of hope and endless possibility as Cassie states: “anyone can fly. All you need is somewhere to go that you can’t get to any other way. The next thing you know, you’re flying among the stars.” This message is a good indication of Ringgold’s outlook on life.

The story of Tar Beach originated with one of Ringgold’s story quilts of the same title. In the early 1970s, Ringgold decided to begin framing her canvases with fabric. Inspired by Tibetan Buddhist paintings known as thangkas, in which images are rendered on silk and bordered with brocade, this framing technique allowed Ringgold to easily transport her large-scale paintings to university exhibitors who began to show interest in her work. On the canvases of her first series framed in the thangkas manner, entitled The Feminist Series, Ringgold wrote messages inspired by the words of influential African American women, including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Shirley Chisholm. This series served as precursor to her story quilts, which she began in the 1980s in collaboration with her mother, Posey, a well-known Harlem fashion designer. As in Tar Beach, the painted quilts include the text of the story inscribed directly on the fabric. These story quilts, though derided as decorative art, linked Ringgold to her African American ancestors. As author Mara Witzling writes: “Ringgold’s use of the quilting tradition is a deliberate statement of her identity as a woman of African-American heritage.” In this manner, Ringgold found her niche with her story quilts, which have become the defining work of her career.

In 1992, Ringgold and her husband moved out of Harlem, settling in Englewood, New Jersey, where the couple bought a ranch house. Ringgold planned to build a studio in the backyard. However, she faced hostile reactions from her predominately white neighbors who hired a lawyer in an effort to prevent her from building the studio. Ringgold believes that her neighbors suspected her proposal to build a studio was a cover for the construction of a structure to rent to boarders. Because her proposal clearly adhered to the neighborhood’s zoning ordinance, Ringgold felt that the reactions of her neighbors were rooted in racial prejudice. To overcome this troubling experience, Ringgold turned to her art capturing the bucolic beauty of her new home. She states: “art is a healer and the sheer beauty of living in a garden amidst trees, plants, and flowers has inspired me to look away from my neighbors’ unfolded animosity toward me and focus my attention on the stalwart traditions of black people who had come to New Jersey centuries before me.” Beginning in 1999, Ringgold created a series entitled Coming to Jones Road, whose quilts allude to the Underground Railroad and the escape of slaves to the north. Representations of the landscape dominate the quilts. However, in Coming to Jones Road 3: Aunt Emmy, the figure of Aunt Emmy fills the canvas her hands crossed in front of her as stares directly at the viewer through her wire-rimmed glasses.

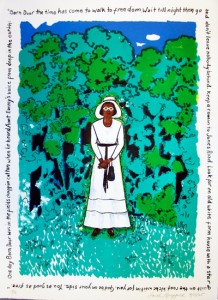

The image of Aunt Emmy resurfaces in the ink-on-paper print done by Ringgold in 2005. Portrayed in the same pose, a younger Emmy stares serenely at the viewer, her simple white dress and hat contrasting with the green that encircles her. The text bordering the print reads: “One day Barn Door was in the fields choppin when he heard Aunt Emmy’s voice from deep in the earth: ‘Barn Door the time has come to walk to freedom. Wait till night then go and don’t leave nobody behind. Keep a comin to Jones Road. Look for an old white farm house with a star quilt on the roof. We be waitin for you. God be on your side. You as good as free.'” Typical of her story quilts, the text integrated into the artwork links the image to a larger narrative. Aunt Emmy urges Barn Door to escape slavery and travel to Jones Road. He will be guided not by the North Star, but the star quilt on the white farmhouse’s roof, a reference no doubt to Ringgold’s home. The powerful image of the lone black woman, a descendant of slaves, surrounded by words of freedom and hope is a testament to the racial and gender discrimination that Ringgold has fought throughout her career.

- Farrington, Lisa E. Faith Ringgold (Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate, 2004), p. 101.

- Ibid.

- Faith Riggold, Tar Beach ( New York: Crown, 1991).

- Faith Ringgold, p. 43.

- Mara W. Witzling, ed., Voicing Our Visions: Writings by Women Artists (New York: Universe, 1991), p. 354.

- Faith Ringgold, p. 96.

- Ibid.

Written by Megan Downing (SC ’08), 2007-08 Academic Year Wilson Intern.